Recently commenter Tiger Mountain raised the parallel between solidarity with Actor’s Equity regarding The Hobbit and support for the mÄori party given their coalition with National and sponsorship of some bad legislation. I explained how they’re not equivalent, but leaving aside the main difference of mandate (which the mÄori party has and AE doesn’t) the wider issue of critical solidarity is an important one, and one which has been raised several times recently. In the wake of The Hobbit fiasco matters of class, identity and solidarity are high in everyone’s minds, and I think in spite of our many differences, we can agree that’s a good thing.

Another contribution to the wider debate is by Eddie at The Standard. For once I find myself agreeing with Eddie’s opening sentence about the mÄori party, which is:

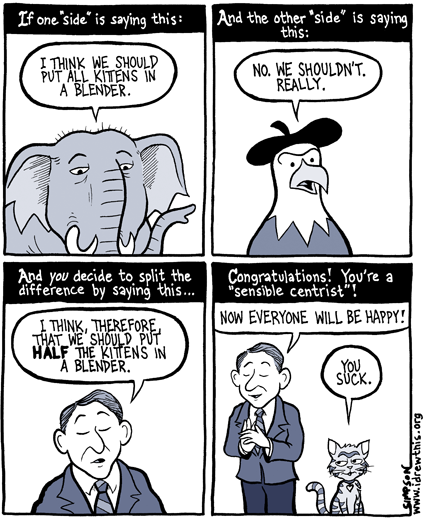

The problem with any identity-based political movement is it pre-supposes that the common identity of its members surpasses their conflicting class interests.

It’s true, although I would have phrased it as follows:

The problem with any class-based political movement is it pre-supposes that the common class of its members surpasses their conflicting identity interests.

I wrote at length about this dynamic tension at a time when it looked like Labour was going to force MÄori to choose between their class identity and their identity as tangata whenua — and how foolish forcing such a choice would be. (It’s still not clear whether Labour has abandoned it, but it at least seems obvious that they don’t have a full-blooded commitment to the blue collars, red necks strategy. But that’s by the way.)

What tends to follow from statements like that one is a series of value judgements about which set of interests ought to take precedence. This can be valuable, but is often tiresome, particularly when those making the pronouncements are “fighting a corner” for only one half of the equation (usually, it must be said, the “class” corner). But Eddie has mostly (not entirely) resisted the urge to do so and focused on the internal dispute within the mÄori party, and in particular the rather dictatorial stance taken by Tariana Turia regarding opposition to the new Marine & Coastal Area (hereafter MCA) Bill. That’s an important debate and examination of it is valuable, but what’s not really valuable is Eddie’s attempt to frame Turia’s stance as a matter of mÄori identity v class identity. It’s not. It’s a matter of the tension between moderate and radical factions within the movement; part of the internal debate within MÄoridom.

Class is an element of this internal debate, but it is not the only element, and I would argue it is not even the predominant element. I think it’s clear that the conciliatory, collaborative, third-way sort of approach to tino rangatiratanga taken by Turia and Sharples under the guidance of Whatarangi Winiata (and whose work seems likely to be continued by new president Pem Bird is the predominant force. I also think the main reason for the left’s glee at the ascendance of the more radical faction is largely due to the fact that there’s a National government at present (and recall how different things were when the boot was on the other foot from 2005-2008). Those leading the radical charge against the MCA bill — notably Hone Harawira, Annette Sykes and Moana Jackson (whose primer on the bill is required reading) are not Marxists or class advocates so much as they are staunch advocates for tino rangatiratanga, who oppose the bill not so much for reasons based on class, but for reasons based on kaupapa MÄori notions of justice. The perspectives of all three are informed by these sorts of traditionally-leftist analyses, but those analyses are certainly not at the fore in this dispute (as they have been in some past disputes). In fact, the strongest (you could say “least refined”) Marxist critiques of the bill advocate for wholesale nationalisation of the F&S, unapologetically trampling on residual property rights held by tangata whenua in favour of collective ownership.

For Eddie’s caricature of the dispute as “identity” v “class” to hold strictly, Turia, Sharples, Flavell and Katene would need to occupy the “authentic” kaupapa MÄori position, the legitimate claim of acting in the pure interests of mana motuhake and tino rangatiratanga; while Harawira, Sykes and Jackson (among others) would need to be largely denuded of this “identity” baggage, and be more or less pure class warriors. Neither is true; Harawira, Sykes and Jackson’s critique of the bill isn’t a Marxist critique; they’re arguing that the bill doesn’t serve the imperative of tino rangatiratanga and is therefore not an authentic kaupapa MÄori position; an assertion that Sharples has tacitly accepted with his response that the Maori Party must accept compromise. (This is true, of course; I agree with Sharples and Turia as far as that goes. I just disagree that this bill is the issue upon which to compromise so heavily. Because of that, I come down on the side of Harawira, Sykes and Jackson.)

The other misguided thing is how Eddie frames Turia’s insistence that Harawira and others adhere to the party line as some sort of manifestation of MÄori over class identity within the party — the quelling of dissent and insistence on loyalty to the leadership elite’s position as a “MÄori” way of doing things, opposed to a “Left” way of doing things. This is absurd. The “left” does not automatically stand in defence of dissent or the public airing of heterodox views, much though Eddie (and I) might wish that it should. As I already mentioned, this is shown by Labour’s response to Turia in 2004 and the mÄori party’s first full term, suspicious at best and hostile at worst. The AE dispute is also an excellent illustration. In that case, the prevailing, “authentic” left position (including that taken by many writers at The Standard, though not — as far as I can recall — by Eddie) was to insist on total public solidarity with the union. In other words, precisely what Turia is insisting upon. I disagreed with this position in AE’s case, and I disagree with it in the mÄori party’s case. Dissent of this sort (or the imperative of its suppression) is not some innate part of “the left”, nor is it absence a characteristic of “identity politics”. It can exist or not in movements of either type, depending on the merits and specifics. It’s my view that such dissent is the beating heart of a movement, and it is peril to quash it. It is a shame that Turia seems to be making the same error as Helen Clark made regarding this issue in 2004.

But despite these objections, ultimately I agree with Eddie about one other thing: the dispute is really interesting, and the emergence of radical critiques and challenges within the movement is exciting and important. The mÄori party has a mandate to agree to the MCA act as drafted; after all, according to Edmund Burke’s famous saying, representatives owe their constituents not only their efforts but their judgement on what is just and right and possible. They’re not elected to always take the easy route of political martyrdom, and because of this they may find themselves staring down their constituents. Sometimes they may win. But nowhere are representatives guaranteed that those constituents must not try to stare back. If those who oppose the bill can raise a hÄ«koi in support of their cause, then let them do so, and more strength to their waewae. And let members of the “left” movements, if their enmity to the bill is genuine, rather than a reflexive attack on a National-led government and the mÄori party orthodoxy which supports it, march alongside them in solidarity. That will be some sort of justice.

L