I heard this phrase when living on a ranch on the Arizona-Mexico border in the early 1990s. It was prompted by my asking a bartender at a local saloon if she felt threatened by the crowd of drunken, armed cowboys in the establishment one evening. In that environment, it made perfect sense (in fact, Arizona has just legislated that a person can carry a concealed firearm without a permit, loosening the laws in force during my time in the state which allowed for the open carrying of firearms without a permit but which required a concealed weapons permit). In fact, on repeated visits to that watering hole I never once saw anyone raise their voice in serious anger.

I mention this because statistics have recently been released that show that the incidence of violent crime in NZ has increased exponentially in the last five years. That has led to the National government talking about “getting tough” on crime along the lines frequently barked by its ACT closet authoritarian partners.

But what does it mean to “get tough” on crime? More incarcerations? Longer sentences? More arrests? More convictions? More confiscations of property? More severe punishments? Reinstitution of the death penalty for heinous crimes? More tasering? Arming the community constables? Expanding the armed offenders squads? Increasing liquor bans in public places?  Having the police using more armed force when dealing with crowd control, gang and other collective disturbances? Increasing youth sentences?

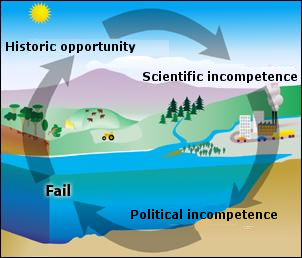

I mention this because “getting tough” on crime, at least when phrased in the above terms, does not address the causal mechanisms behind the upsurge in violent crime (which I agree has increased and now become a serious pathology in NZ civil society). One can seek explanations for causes in many places: exposure to media-provided violence at a young age, dysfunctional familities, bullying culture, the pervasive influence of alcohol, the long-standing tradition of civil disobedience and passive resistance practiced by some communities and individuals, now taken to new extremes, the degeneration of popular and civic culture into venal self-absorption–the list of possible causes is long. But what does “getting tough” have to do with any of these possible causes? Unless a more draconian criminal system is seen as a deterrent to violent crime (and there is much dispute about the deterrent value of things such as capital punishment), how exactly is “getting tough” on crime going to solve the problem?

I must confess to being of two minds, because as an immigrant from the US I have always felt that punishment for serious offenses was a bit of a joke in NZ and that there are not enough resources dedicated to crime-fighting  (in fact, I still believe that NZ is a country where one can literally get away with murder if cunning and meticulous). But I also know that the “tougher” US approach to crime also has done little to nothing to drive down crime rates (in fact, the “broken windows” approach to petty crime adopted in New York City in the 1990s, and in which worked marvels in lowering the overall crime rate in that city, was focused on early intervention at the lower end of criminality rather than on increased punishment for more serious offenses). Instead, US violent crimes rates, not surprisingly, lowered as the economy expanded in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and, not surprisngly, have increased since the recession began to bite hard in 2008. Which is to say, although the violence of socio and psychopaths is unaffected by economic cycles, much of the residual acts of violence tend to overlap with economic downturns when unmitigated by early intervention or causal prevention schemes.

Which brings back the cause-effect–response syllogism mentioned earlier. There is a reason why that crowd in the border town saloon was armed. At the time there were only 2 sherriff’s deputies avaliable to patrol over 1000 square miles of national forest and ranchland strung along the border and extending some 20-50 miles northward. Besides the various stinging and biting small critters and large predators (bears, big cats) that stalked the Sonoran high plateau and mountain ranges in which our properties were located, there were human dangers emanating from across the border as well as from within Arizona itself (organised crime drug smuggling and survivalist militas, respectively). Absent the protection of the state in such remote locales, people actually practiced the concept of self-defense because to not do so invited serious victimisation, often of a terminal sort. As the saying goes, the best home insurance policy one can have in such a personal threat environment is the sound of a pump action shotgun chambering a buckshot round. The point being, that armed crowd had reason to be so given the causal mechanisms at play in that particular crime environment (which I must say, remains one of the most beautiful landscapes I have had the pleasure to experience first hand). Unfortunately, perhaps, things changed after 9/11 and the region is now swarming with Border Patrol, National Guard, roadblocks, fences, audiovisual sensors and motion detectors as well as increased numbers of north-bound migrants, to the point that many long-term residents have moved away in search of solitude and workable land. It turns out, at least in that regard, I left just in the nick of time.

That brings me back to NZ, my adopted home since 1997 and in which I have seen a steady decline in civility during the last decade that is now confirmed by crime statistics. Not being a criminologist or a social welfare expert, I cannot offer any concrete prescriptions, much less a panacea for the upsurge in criminal violence now afflicting Aotearoa. But what I can say is that it does no good to play the role of chickenhawk or attack poodle by fulminating about getting tough on crime without linking the thirst for punishment to an understanding of what drives violence and insecurity in the first place. In fact, until the latter is identified, addressed and ameloirated, then the former is just another way of pouring salt into a gaping wound.