I was invited to speak at a forum in Wellington on the “Privacy Security Dilemma.” It included a variety of people from government, the private sector, academia and public interest groups. The discussion basically revolved around the issue of whether the quest for security in the current era is increasingly infringing on the right to privacy. There were about 150 people present, a mixture of government servants, students, retirees, academics, foreign officials and a few intelligence officers.

There were some interesting points made, including the view that in order to be free we must be secure in our daily lives (Professor Robert Ayson), that Anglo-Saxon notions of personal identity and privacy do not account for the collective nature of identity and privacy amongst Maori (Professor Karen Coutts), that notions of privacy are contextual rather than universal (Professor Miriam Lips), that in the information age we may know more but are no wiser for it (Professor Ayson), that mass intrusions of privacy in targeted minority groups in the name of security leads to alienation, disaffection and resentment in those groups (Anjum Rahman), and that in the contemporary era physical borders are no impediment to nefarious activities carried out by a variety of state and non-state actors (various).

We also heard from Michael Cullen and Chris Finlayson. Cullen chaired the recent Intelligence Review and Finlayson is the current Minister of Security and Intelligence. Cullen summarised the main points of the recommendations in the Review and was kind enough to stay for questions after his panel. Finlayson arrived two hours late, failed to acknowledge any of the speakers other than Privacy Commissioner John Edwards (who gave an encouraging talk), read a standard stump speech from notes, and bolted from the room as soon as as he stopped speaking.

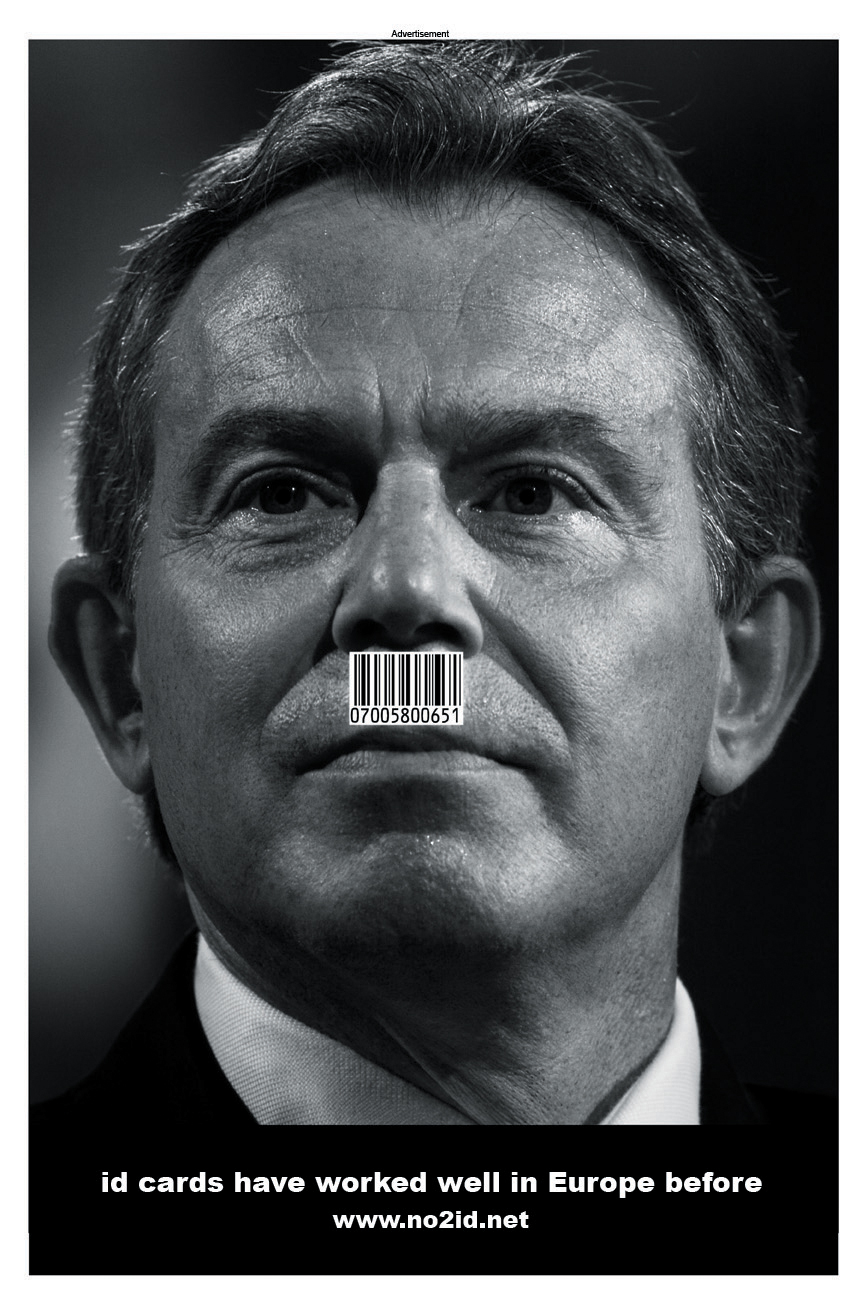

Thomas Beagle gave a strong presentation that was almost Nicky Hageresque in its denouncement of government powers of surveillance and control. His most important point, and one that I found compelling, was that the issue is not about the tradeoff between security and privacy but between security and power. He noted that expanded government security authority was more about wielding power over subjects than about simply infringing on privacy. If I understand him correctly, privacy is a commodity in a larger ethical game.

Note that I say commodity rather than prize. “Prize” is largely construed as a reward, gain, victory or the achievement of some other coveted objective, especially in the face of underhanded, dishonest, unscrupulous and often murderous opposition. Â However, here privacy is used as a pawn in a larger struggle between the state and its subjects. Although I disagree with his assessment that corporations do not wield power over clients when they amass data on them, his point that the government can and does wield (often retaliatory) power over people through the (mis) use of data collection is sobering at the very least.

When I agreed to join the forum I was not sure exactly what was expected from me. I decided to go for some food for thought about three basic phrases used in the information gathering business, and how the notion of consent is applied to them.

The first phrase is “bulk collection.” Bulk collection is the wholesale acquisition and storage of data for the purposes of subsequent trawling and mining in pursuit of more specific “nuggets” of actionable information. Although signals intelligence agencies such as the GCSB are known for doing this, many private entities such as social media platforms and internet service providers also do so. Whereas signals intelligence agencies may be looking for terrorists and spies in their use of filters such as PRISM and XKEYSCORE, private entities use data mining algorithms for marketing purposes (hence the targeted advertisements on social media).

“Mass surveillance” is the ongoing and undifferentiated monitoring of collective behaviour for the purposes of identifying, targeting and analysing the behaviour of specific individuals or groups. It is not the same thing as bulk collection, if for no other reason than it has a more immediate, real-time application. Mass surveillance is done by a host of public agencies, be it the Police via CCTV coverage of public spaces, transportation authorities’ coverage of roadways, railroads and airports, Â local council coverage of recreational facilities and areas, district health board monitoring of hospitals, etc. It is not only public agencies that engage in mass surveillance. Private retail outlets, shopping centres and malls, carparks, stadiums, entertainment venues, clubs, pubs, firms and gated communities all use mass surveillance. We know why they do so, just as we know why public agencies do so (crime prevention being the most common reason), but the salient fact is that they all do it.

“Targeted spying” is the covert or surreptitious observation and monitoring of targeted individuals and groups in order to identify specific activities and behaviours. It can be physical or electronic (i.e. via direct human observation or video/computer/telephone intercepts). Most of this is done by the Police and government intelligence agencies such as the SIS, and most often it is done under warrant (although the restrictions on warrantless spying have been loosened in the post 9/11 era). Yet, it is not only government security and intelligence agencies that undertake targeted spying. Private investigators, credit card agencies, debt collectors, background checking firms and others all use this as a tool of their trades.

What is evident on the face of things is that all of the information gathering activities mentioned here violate not only the right to privacy but also the presumption of innocence, particularly the first two. Information is gathered on a mass scale regardless of whether people are violating the law or, in the case of targeted spying, on the suspicion that they are.

The way governments have addressed concerns about this basic violation of democratic principles is through the warrant system. But what about wholesale data-gathering by private as well as public entities? Who gives them permission to do so, and how?

That is where informed consent comes in. Informed consent of the electorate is considered to be a hallmark of robust or mature democracies. The voting public are aware of and have institutional channels of expression and decision-making influence when it comes to the laws and regulations that govern their communal relations.

But how is that given? As it turns out, in the private sphere it is given by the phrase “terms and conditions.” Be it when we sign up to a social media platform or internet service, or when we park our cars, or when we enter a mall and engage in some retail therapy, or when we take a cab, ride the bus or board a train, there are public notices governing the terms and conditions of use of these services that include giving up the right to privacy in that particular context. It may be hidden in the fine print of an internet provider service agreement, or on a small sticker in the corner of a mall or shop entry, or on the back of a ticket, but in this day and age the use of a service comes attached with it the forfeiture of at least some degree of privacy. As soon as we tick on a box agreeing to the terms or make use of a given service, we consent to that exchange.

One can rightly argue that many people do not read the terms or conditions of service contracts. But that is the point: just as ignorance is no excuse for violation of the law, ignorance of the terms of service does not mean that consent has not been given. But here again, the question is how can this be informed consent? Well, it is not.

That takes us to the public sphere and issues of governance. The reality is that many people are not informed and do not even think that their consent is required for governments to go about their business. This brings up the issue of “implicit,” “implied” or inferred” consent. In Latin American societies the view is that if you do not say no then you implicitly mean yes. In Anglophone cultures the reverse is true: if you do not explicitly say yes than you mean no. But in contemporary Aotearoa, it seems that the Latin view prevails, as the electorate is often uninformed, disinterested, ignorant of and certainly not explicitly consenting to many government policy initiatives, including those in the security field and with regards to basic civil liberties such as the right to privacy and presumption of innocence.

One can argue that in representative democracy consent is given indirectly via electoral processes whereby politicians are elected to exercise the will of the people. Politicians make the laws that govern us all and the people can challenge them in neutral courts. Consent is given indirectly and is contingent on the courts upholding the legality if not legitimacy of policy decisions.

But is that really informed contingent consent? Do we abdicate any say about discrete policy decisions and legislative changes once we elect a government? Or do we broadly do so at regular intervals, say every three years, and then just forget about having another say until the next election cycle? I would think and hope not. And yet, that appears to be the practice in New Zealand.

Therein lies the rub. When it comes to consenting to intrusions on our privacy be they in the private or public sphere, we are more often doing so in implicit rather than informed fashion. Moreover, we tend to give broad consent to governments of the day rather than offer it on a discrete, case by case, policy by policy, law by law basis. And because we do so, both public authorities and private agencies can collect, store, manipulate and exchange our private information at their discretion rather than ours.