Military politics as a distinct “partial regime.”

Notwithstanding their peripheral status, national defense offers the raison d’être of the combat function, which their relative vulnerability makes apparent, so military forces in small peripheral democracies must be very conscious of events happening in the world around them. At the same time, the constitution and deployment of military forces is a part and product of national political history and domestic considerations. Specifically, the dynamics of having to balance force flexibility, political ideology, popular consent and international security commitments constitute the crucible within which national military politics is forged. It is the vessel in which external strategic necessities give body to specific policy rationales and practices, or what can be called the military politics “partial regime” (Schmitter, 1993).

In turn, this core area of state activity can be disaggregated into its component parts. Military politics involves three analytically distinct fields that, although addressed separately by the literatures on military science, sociology and warfare, are seldom examined together. At one level, lines of division are drawn between those who write as generalists versus those who write as specialists. Generalists focus on comparative civil-military relations, while on the other hand specialists focus on military organization and geopolitical strategy. One side looks at the relationship of the security community (mostly that of its military apparatus) with civilians holding positions in and out of power The other side looks at the logic and organization of the military apparatus itself. Comparative scholars who study civil-military relations operate at the macro level of analysis. Those who study military and geopolitical strategy focus on the meso-analytic level. Those who study military organization and tactics dwell on the micro-level of military politics.

The generalist literature concentrates on issues of control, influence or relationship of the national security apparatus with civilian political society, the institutional features of which make for broad typologies of civil-military relations. The question of how specific civil-military relations impinge on organizational and strategic aspects of military politics is seldom addressed. Here we look at at the interrelated features of all three approaches in a cross-regional section of small peripheral democracies after the Cold War.The approach is novel for several reasons. The field of comparative politics is dominated by regional comparisons based upon linguistic, ethnic, constitutional, cultural, political or geographic proximity. The specialist literature on military affairs is divided into organizational and strategic analyses. In neither sub-field is it common to engage in cross-regional comparisons, much less coupled with an analytic perspective that cuts across the generalist versus specialist dichotomy. This project bridges the sub-disciplinary divide as part of an extended methodological and conceptual introduction to the case studies.

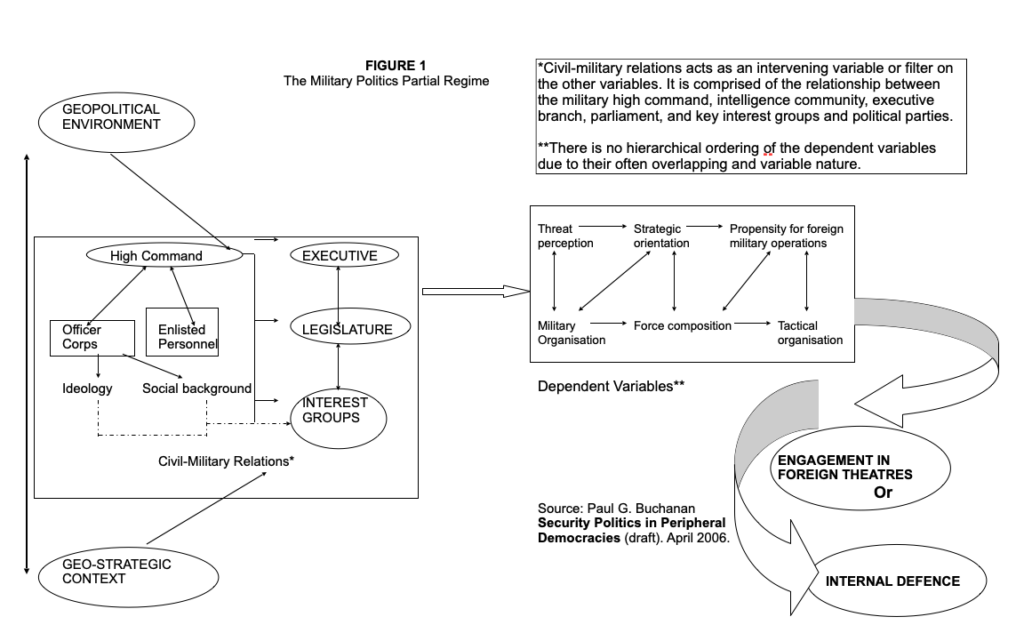

The argument put forth is that military politics is more than the sum of its parts, nor is it just concerned with “military affairs.” Rather than a piecemeal treatment that highlights some features while ignoring others, the intent is to adopt a holistic approach that addresses the distinct aspects of military politics by dividing it into four issue areas instead of the three-fold division mentioned above. The four issue areas are civil-military relations (which examines the relationship of the military with the national political regime); force composition (comprised of organizational hierarchy, budget, personnel, training and equipment); geopolitical perspective (including geo-strategic context, strategic culture, threat perception, net assessment and risk projection); and force deployment (where, why and under what type of operational command and control). Having examined the particulars of each, the four issue areas can be summarized in order to provide an overview of the major features of military politics in each case. In doing so a more comprehensive picture can be drawn of the rationales and impact of the external security approaches adopted by the countries under scrutiny.

As an example of why a more integrated approach to the subject of military politics is necessary, consider briefly some of the issues involved in the study of one of its component parts or issue areas: civil-military relations. Most of the specialist literature on comparative civil-military relations focus on the relationship between military and civilian political elites, or on the relationship of the military as an institution with civilian political institutions. The impact of civil society on these relations is seldom and then only tangentially discussed. But the issue has more depth than conventional wisdom would suggest.

Consider that New Zealand lost the protection of the ANZUS (Australia-New Zealand-United States) military alliance once it declared itself, over the objections of the military high command but riding a broad wave of popular support, a nuclear-free state in 1985. This forced reconfiguration of the New Zealand Defense Forces (NZDF), which now largely relies for military assistance and intelligence on Australia even if its military ties with the US have strengthened since 9/11. Today New Zealand reliance on Australia is expected in the event of external aggression against its national territory as well as seen in the military and logistical assistance for New Zealand troops deployed in regional theaters such as Afghanistan, Iraq, East Timor and the Solomon Islands. Although it is the cause of some professional embarrassment, the NZDF largely configures its forces to operationally mesh with Australian units. Beyond that, New Zealand has banked heavily on its strong commitment of troops to United Nations peacekeeping operations paying mutual defense dividends in the event that it is subject to external aggression. The government sees the Army as a peace keeping and humanitarian assistance force, with the Navy and Air Force largely confined to coastal defense and multilateral support roles (e.g., freedom of navigation exercises). The public remains largely disinterested in military-security affairs, and when it does focus on the subject it tends to be in reaction to civilian partisan disputes over defense policy.

In recent years Islamicist terrorism has dominated the threat perspectives the NZ intelligence community (NZIC) and military planners, leading to support for involvement in the anti-jihadist campaigns in Afghanistan (as part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission authorised by the UN) and Iraq (as part of the post-Hussein effort to impose political order in Iraq and prevent the establishment of an Islamic caliphate in its territory). This orientation also dominated local security-intelligence perspectives, at least until the March 15, 2019 white supremacist terrorist attacks in Christchurch that killed 51 people and injured over 100 others. At that point the NZIC was forced to take a serious look at itself and the assumptions and methods (and biases) that underpinned their threat assessments until that day.

For its part, Portugal has a long tradition of alliance with the largest maritime power in the Atlantic, first the United Kingdom, then the United States, which influenced the military strategic perspective confronted by three different threat scenarios during the latter part of the twentieth century. These were the Portuguese colonial wars, the Cold War, and the War on Terror. The first scenario ran in parallel to the interests of the maritime patrons during the Cold War, and was prosecuted with their support because the colonial struggles in Lusophone Africa were seen as part of the global conflict between the Western and Soviet blocs (as proxy wars). This made for a relatively tight alliance in which Portugal recognized its role as a subordinate partner to the US and in which the US and other Western nations overlooked its authoritarian political features in exchange for military assistance to the declining empire.

The Portuguese military perspective began to shift in the 1970s with the loss of the colonies and subsequent regime transition to democracy in the Portuguese “metropolis.” That was followed by the increased economic integration of Europe, the decline of the Soviet bloc, and the rise of Islamicist armed struggle flowing on the heels of greater economic and human interchange between Portugal and the Arab world. These shifting conditions made for a very different domestic and international context in which Portuguese military politics were formulated. The effects of these changes are ongoing but have, among other things, seen recent emphasis on land-based peace keeping roles that reversed the maritime interdiction priorities that had been the hallmark of the post-colonial Cold War strategic perspective. This led to disagreements between the Portuguese Army, on the one hand, and the Air Force and Navy, on the other, about the proper thrust of Portuguese strategic policy. The government wavers between territorial defense and extra-territorial mission orientation.

In contrast, after a period of post-authoritarian hyper-politicization in the 1970s in which all issues of policy were the subjects of popular debate, the Portuguese public remains largely disinterested in the subject of national defense. The majority sees the proper role of the armed forces as humanitarian and logistical assistance at home and abroad, followed by multinational peace keeping duties.

This raises a noteworthy point. In many democracies, civilians and the military high command responsible for defending them often do not share perceptions of threat. For peripheral democracies, the differences in threat perception can be acute. Portuguese and New Zealand public opinion sees very little in the way of direct external threats, especially if the countries steer clear of foreign entanglements such as the “War on Terror.” There is a strong current of neutralism in both countries in spite of their overwhelming identification with the West, and both have significant isolationist elements among the public at large. Civilian political leaders are more attuned to larger geostrategic and diplomatic realities, but these do not necessarily translate into convergence of perspective with military strategic planners.

As an illustration, the Portuguese Navy wants submarines as a priority for maritime interdiction purposes while the Army wants more troops for multilateral operations, while the New Zealand Air Force similarly wants tactical combat aircraft for air defense and the Navy wants an upgrading of the blue water component of its fleet. The civilian political elite and public in both countries cannot see the reason why. This divergence of views between unformed personnel and civilians makes for a very different set of civil-military relations than in countries where threat perceptions or at least public opinion on the proper role of the armed forces coincide or are relatively proximate.

Such is the case with Chile and, as an extended example, Fiji. In Chile the elected political elite installed after 1990 have insistently pushed for military re-orientation towards international peace keeping operations, whereas the military high command and public opinion continue to view territorial defense as a primary focus of the armed forces. In Fiji the political and military elite tend to agree on the international role but disagree on the domestic responsibilities of the armed forces, something that is reflected in the views of the ethnic groups from which each is in the majority drawn. The larger issue is that civil-military relations is a multi-faceted phenomena that operates both dialectically and synergistically, something that colors the other aspects of the military politics partial regime.

A schematic representation of the military politics partial regime for any given country that covers the way in which the four issue areas (and their component parts) combine can be depicted as follows:

FIGURE 1: The Military Politics Partial Regime

The specific mix of the four issue areas makes for variations in military politics between regime types (authoritarian, democratic) depending on the way in which they are integrated and related. Changes in geopolitical conditions and geostrategic context have an impact on national civil-military relations. The latter are rooted in the specific power relationship between civil society, political society and military society. As a result, different types of civil-military relations respond differently to the external contextual shifts with specific security perspectives and institutional morphologies. This is seen in the organization, strategic doctrine, equipment and physical deployment of their respective militaries over time.

Variance is not just seen at the level of regime types. It also occurs within regime types, and across the sub-types of each (e.g. between parliamentary versus presidential democracies or between bureaucratic-authoritarian and national-populist regimes, to say nothing of post-revolutionary regimes such as Cuba, Iran or Vietnam). Although undoubtedly a worthy subject, here the focus is not on variations in authoritarian military politics. Instead, by examining a small-N cross-regional sample from Australasia, Southern Europe and the Southern Cone, the project seeks to demonstrate how historical and institutional factors at the national level combine with the geostrategic context to make for recent variation in the military politics of small peripheral democratic regimes. The general conclusions may turn out to be intuitive, but the specific process and nature of change makes for difference within the sample, which in turn makes for variance in the specific explanation for each.

NEXT: The “double shocks” in international security affairs.