The matters I discussed in the previous post to do with reality-adjacent campaigning are about targeting voters with messages they can grok about issues they care about. But empiricism is not much good for deciding a party’s ideological values or for developing policy. Parties made up of committed ideologues remain indispensable for that reason.

As is often pointed out to me, I am not such a person. I have never been a member of a party, nor involved in a campaign, and I have little desire to do either. For some people this means I obviously don’t know what I’m talking about; fair enough. As an analyst, I prefer the outsider’s perspective. I don’t feel any pressure to be loyal to bad ideas or habits, and I try to answer only to the evidence. Ironically, though, there isn’t much hard evidence for the arguments I’m about to make about the medium-term future of the NZ left. Nobody has any. It’s value-judgements all the way down. So my reckons are as good as anyone else’s, right?

“That doctrine of the Little Vehicle of yours will never bring the dead to rebirth; it’s only good enough for a vulgar sort of enlightenment. Now I have the Three Stores of the Buddha’s Law of the Great Vehicle that will raise the dead up to Heaven, deliver sufferers from their torments, and free souls from the eternal coming and going.â€

— Bodhisattva Guanyin, Journey to the West

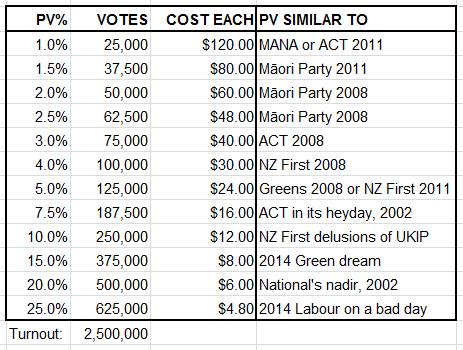

For mine, the major shift from the 2014 election — apart from the unprecedented dominance of the National party — is away from Small Vehicle politics and towards Big Vehicle politics. Only National and NZ First gained modestly. All other parties all failed to meet the threshold or lost support. The destruction of Internet MANA and the failure of a much-improved Conservative party demonstrates that there is no tolerance for insurgency, and the cuts to Labour and the Greens indicates that any confusion or hinted shenanigans will be brutally punished. National can govern alone; it is including ACT, United Future and the MÄori Party as a courtesy, and to provide cover. This is Key’s money term. It should be a period of grand political themes and broad gestures, and the left needs to attune itself to this reality: Labour needs to take the responsibility of being a mass movement with broad appeal and capability; a Big Vehicle. The Greens will hopefully get bigger, but I think they will remain a Small Vehicle, appealing to relatively narrow interests, however important they are.

Assuming it doesn’t annihilate itself utterly in the coming weeks, Labour will be the core of any future left-wing government, but the strategies that served it poorly as a substantial party of opposition will be utterly untenable in its diminished state. Throughout most of the past six years, Labour has been the party opposed to National. They haven’t been a party that clearly stands for anything, that projects the sort of self-belief that National, the Greens, and even NZ First does.

Labour therefore needs to re-orient its conduct and messaging to its core values, and those are fundamentally about secure and prosperous jobs for the majority of working people, and those who rely on the state as the provider of last resort. But I am emphatically not calling for a retreat to doctrinaire materialism at the expense of superstructural considerations. The demographic groups that kept Labour alive this election were women (6.6 points higher than men), MÄori, and Pasifika, and the party would be insane not to recognise the debt that they owe these voters. Of 11 MPs in whose electorates Labour won the party vote, only one — David Clark — is PÄkehÄ, and in his electorate of Dunedin North Labour got 24 votes more than National. Five (Williams, Mahuta, Sepuloni, Wall, and Whaitiri) are women. The return of Te Tai HauÄuru, TÄmaki Makaurau and especially Te Tai Tokerau to Labour underscores the opportunity that exists to reconnect with MÄori.

There will be enormous pressure to begin taking these voters for granted again, and it must be vigorously resisted. As for talk of reaching out to “the base” — a party’s “base” is who votes for it when it is at its lowest. Labour’s base as demonstrated by the 2014 election is comprised largely of working-class women, MÄori, and Pasifika. So policy proposals that impact those groups more directly — parental leave, free healthcare, ECE, support for family violence services, social welfare — should not be neglected. By and large, though, these voters will also be motivated by many of the same concerns that speak to anyone else, particularly as the National government’s policies begin to bite. But the party’s appeal must expand well beyond this base into the centre ground. It need not be zero-sum. Labour cannot afford to be caricatured as a party that only cares about those groups, it must be a party that a broad range of people feels like it could vote for — like the party understands their needs, and would act in their interests. The key is framing messages and policies in ways that speaking to the base without alienating the broader public, and to the broader public without excluding the members of these base demographics groups, using separate channels and emphasis where necessary. The key term here is “emphasis”.

The party also has to be smarter and more pragmatic than it has been, especially in social policy. At a minimum, this means an end to opposing WhÄnau Ora on principle. The new MP for HauÄuru, Adrian Rurawhe, speaking to Radio New Zealand’s Te Ahi KÄ on Sunday, has a strong line on this: to not attack the philosophy, to not attack the model, but to attack the implementation of individual schemes. There’s a distinction between cartelised privatisation of service delivery, and self-determination, and a party of MÄori aspirations should work, even in opposition, to strengthen and entrench the latter so it can succeed. National has spent six years making policies targeted at MÄori, run by MÄori and under MÄori delivery models politically and culturally acceptable, and has made enormous progress on Treaty claims. Labour must capitalise on these gains. They also provide an opportunity to reach out to the MÄori Party, should they survive another term in government and remain viable.

The same imperative also means collaborating with the government on distasteful topics like RMA reform, regional and rural development, and charter schools. The battle over whether these will happen is comprehensively lost; the questions now are how badly are they going to be done, and how much political capital will be wasted in trying to unshit the bed later. Better for Labour to work collaboratively with the government to limit the damage and make the best possible use of the rare opportunity to reform entrenched systems. Let the Greens fight them. Don’t worry! There will be plenty else to oppose.

The Greens are here to stay, and Labour should not be reluctant to bleed some of its liberal-activist support to them, to make up bigger gains elsewhere. This will infuriate many in the activist community, and most everyone on Twitter, but my sense is nearly all of those folks vote Green anyway, and they will be in safe hands. Labour hasn’t been a radical or activist party in recent memory, except for 1984-1990, and we know how that turned out.

There is an opportunity to coordinate and make use of the temperamental differences between the parties, with the Greens taking a more vigorously liberal and activist role against Labour’s moderate incrementalism. The strategy that has been proposed intermittently for ages that Labour should attack the Greens directly is insane — the two parties, while allied, do not and should not substantially share a constituency. Labour, like National, is is a mass movement of the people, and should become more so; the Greens are a transitional insurgent movement seeking to influence the existing mass movements, and they seem intent on continuing in that role.

Of all the Small Vehicles, the Greens are best equipped to thrive in a Big Vehicle-dominant context. New Zealand First will struggle. While Labour should collaborate with the Greens, Labour should contend with NZ First, and aim either to gut it of its voter base or, more plausibly, to drive it towards National where the inevitable contradictions and ideological enmities will probably cause harm to both parties. ACT and United Future are wholly-owned by John Key and are effectively irrelevant.

The worst case for Labour, apart from continuing in the blissful ignorance that nothing is really wrong, would be a retreat into sullen populism, trying to out-Winston Winston or out-Key Key, or chucking the vulnerable passengers overboard so that the ship might float a little higher in the water for those who remain. The party has to have its own identity and its own motive force, and it has rebuild its own constituency. It can be done. I hope they can do it, because we haven’t had an effective Labour party for a long time now, and we really need one.

L