So the mÄori party has accepted the government’s Foreshore and Seabed Act repeal proposal.

As I posted the other day, the Iwi Leadership Group, chaired by Mark Solomon, was dead-set against the proposal, with Solomon speaking in very strong terms against it. But now, while residual concerns remain, the ILG has now issued an admittedly grudging and vague endorsement. But there is a lot of daylight between Solomon’s words previously and the content of this acceptance. So my question is: what’s changed? While writing this, I was pleased to hear that Brent Edwards and Barry Soper asked the same thing during the PM’s presser. According to Turia, what changed is that:

In terms of customary title and customary rights, we have been given an assurance that those rights will be as sacrosanct as any other rights to title.

That’s very squishy. The problem hasn’t really been the veracity of the rights in question; it’s been the barriers to their acquisition and the limitations on their extent. Neither of those problems have been addressed. The matter of ownership isn’t trivial, and in particular the glaring difference between nascent MÄori title-holders whose potential rights have been largely circumscribed while the possessions of existing, mostly PÄkehÄ, title-holders are retained, was of particular concern to Mark Solomon — has not been addressed. More than that, the requirement that claimants not be disadvantaged in their claims by a prior Treaty breach is nowhere to be seen. This is particularly crucial, since it distinguishes to an extent between legitimate and illegitimate alienation. Under such a proposal (as I understand it, and in general) a claimant would be able to claim rights to privately-owned raupatu land and resources, whereas under the present scheme any land in private ownership — no matter whether it was originally confiscated at gunpoint — cannot be subject to a claim. That’s a big deal.

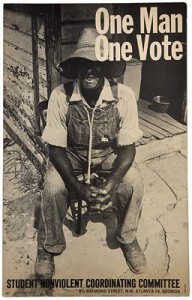

There are some positives in this scheme. As I’ve said, I dislike the “public domain” aspect of it; but I think the recognition of two distinct levels of customary title is good (particularly when set against the FSA’s draconian all-or-nothing approach in which all would get nothing). I generally approve of the mechanisms by which those claims can be tested. But it’s my view that this proposal grants little to MÄori that they didn’t already have under the FSA, and although the barriers to test a claim are lower, and the mechanisms are more robust, and there’s generally better faith between the crown and MÄori now than there was in 2004, it’s fundamentally the same sort of beast: iwi petition the Crown for rights that, according to the common law of the land, were never extinguished and ought never have been abridged; MÄori debased as supplicants, begging the very agent of the crimes perpetrated against them for recompense.

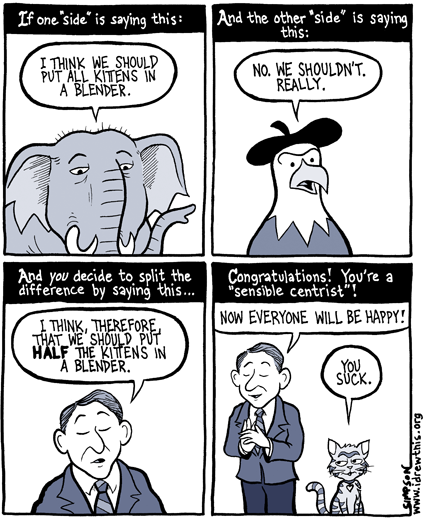

Anyway, my initial position of criticism in the former post was that the mÄori party would be acting against their mandate if they accepted the government’s offer, it having first been unanimously rejected by the ILF. But the ILF having turned on a dime leaves me in two minds: I don’t like this proposal and I don’t think it has sufficient merit to be acceptable to MÄori; but regardless of that the mÄori party is fulfilling its mandate by accepting it, acting in accordance with the guidance given it by the Iwi Leadership Forum as representatives of the iwi groups with claims to test. What puzzles me is not why the mÄori party have agreed to it — although the blame will no doubt be laid at their feet more than anyone else’s, and I agree that they ought to have done better — but why the ILF changed so rapidly and so completely. I’m left feeling much like I did when Michael Laws claimed victory about the h when the result of the government’s decision would be to establish Whanganui as a new orthodoxy, and relegate those wanting to use Wanganui to quirky outsider status:

Who knew that all Michael Laws wanted for his cause was an emasculating partial endorsement and a prolonged death sentence? He could have saved everyone (and his own reputation) a great deal of trouble by making this plain at the beginning.

There are a few possible explanations. One is that Solomon’s position as articulated on the Sunday politics shows and later on NatRad was not truly representative of the ILG’s position, and he has since been hauled back into step. DPF favours this line of argument and reproduces a NgÄti Porou press release in evidence. Another is that Solomon’s remarks were an aggressive negotiating position. But he’s not usually the sort to play brinksmanship games, and this government, with its solid parliamentary majority and two-winged coalition structure, is a poor choice of target for such a strategy. Another possibility is that something really did change, and they’ve received more than just assurances. A fourth, and no doubt very popular possibility is that Turia, Sharples, Solomon, Mahuika and all the other Hori Tory tribal elites have been bought off with baubles of office, beads, blankets and limousines.

I guess we’ll see when the final bill is drafted and introduced. And, of course, the response from the flaxroots will be important, because if they feel like they’ve been sold down the river, no amount of baubles will keep them from abandoning the mÄori party. And nor should they.

L