The past week has illustrated in clear terms the New Zealand Labour party’s decline as an effective opposition party. In the opening moments of election year 2011, John Key has stepped up to demonstrate the full extent of the National government’s apparent impunity. He has done this in three ways.

First, by fronting Morning Report, Nine to Noon, Campbell Live and other tier-1 hard-news media to outline his intention to partially privatise SOEs. Privatisation, since the Fourth Labour Government, has been a ‘third rail’ issue; one the NZ left is unequivocally opposed to. By going into bat for privatisation personally, and in considerable policy detail, Key confounded criticism which has been (justly) levelled at him throughout the electoral term so far that he often refuses to show up on hard media, while continuing to keep regular spots in soft formats like Breakfast, and on less rigorous media such as Newstalk ZB. He also invested his own (considerable) political capital in the enterprise, making privatisation a matter of his own judgement and credibility.

Second, he sought out and is revelling in the controversy caused by his “Liz Hurley is hot” stunt, undertaken on Radio Sport with convicted back-breaker Tony Veitch. In political terms, the first bit was no meaningful risk; Key has played the ‘frankly, I’m a red-blooded Kiwi bloke’ card several times before, always to good effect, and most notably when he informed a press scrum he’d had a vasectomy. The decision to undertake an interview with the disgraced Veitch was a considerably more risky proposition because of the nature of Veitch’s offending against his partner, combined with the subject matter of their conversation, and the fact that Key’s political appeal to women has been considerably stronger than previous National leaders. This seems clearly calculated to demonstrate what he can get away with; and the gamble has in fact paid off so well that Phil Goff today felt compelled to follow suit, suggesting a slightly sad “me too, me too” narrative.

The third of Key’s big moves was today’s dual announcement that the election would be held on 26 November, 10 months away and following the Rugby World Cup; and that he would not consider a coalition arrangement which included Winston Peters. Coupled with ruling out working with Hone Harawira outside his present constraints in the mÄori party, this declaration will provide considerable reassurance to National’s traditional base, and will scotch any possibility of wavering conservatives casting a hopeful vote for Winston Peters as an each-way bet. It is a risky proposition, though — Peters remains a redoubtable political force, and it is not beyond possibility that he returns to parliament. However I think Key has read the electorate well; he knows that while a small number of people love Peters, and a small number loathe him, many of those in the middle are vaguely distrustful of him. As Danyl points out, he’s managed to link Peters to Goff in a way which emphasises both leaders’ worst attributes: Peters’ polarising tendency, and the general unease and disdain with which voters view Goff. The decision to call the election so early is also bold. It means relinquishing the incumbent advantage of being able to control the electoral agenda; being able to determine when ‘government as usual’ ceases and ‘campaign season’ begins. This is an intangible but valuable benefit, and it has been traded off against another piece of reassurance: the sense that Key and his government are “playing it straight” with the New Zealand public; that they intend to run an open and forthright campaign and to seek an honest mandate for their second term. The choice of election date isn’t entirely selfless, of course — the All Blacks are odds-on favourites to win the Rugby World Cup, and even if they don’t, the tournament, its pageantry and excitement and revenue boost will bifurcate the campaign. The traditional campaign period will mostly be drowned out by this event, save for the last few frantic weeks.

In most election years, swapping agenda-setting rights for a “playing it straight” feeling would be a poor tradeoff. In most election years, a sexist stunt with a known and publicly reviled wife-beater would be a poor start. In most election years, running a campaign based on privatisation would simply be a non-starter. While the paragraphs above read somewhat like breathless praise of Key’s status as a political playa, that’s not my intent. I think he’s good, but mostly John Key just knows what he can get away with. The reason he can get away with all of these things is because there is no credible opposition to prevent him from doing so. Anyone half-decent can look sharp when playing against amateurs.

It has been Labour’s job to prevent the government from reaching the state of near-impunity they now enjoy, and their failure to do so means there is now a real danger that Key will get the genuine and sweeping mandate he seeks. To a considerable extent they were doomed in the task of preventing this from the outset, because they didn’t think it was possible that he’d ever achieve it. Clark Labour throughout 2008 fundamentally misunderestimated Key, writing him off as a bumbling lightweight, and this was a crucial error. Since well before the election — this example is from July 2008 — I’ve been arguing to anyone who’ll listen that instead of taking easy pot shots at Key based on his weaknesses, any critique should focus on his strengths. Quoting myself, from the above:

Key’s strengths [per the Herald bio], which enabled him to succeed as a currency trader: Decisiveness. Determination. Patience. Ice-cold calm under fire. Willingness to risk it all. Ability to follow through. Remorselessness.

If you want to attack John Key, draw attention to what might happen under a Key government. Given his history, he’s not some motley fool who won’t make sweeping changes – he hasn’t gotten where he is today by being timid. I think he has the wherewithal to roll out a sweeping programme of political and social change the like of which we haven’t seen since Lange, but I think that, unlike Lange, he won’t get cold feet. If you don’t like Key’s politics, I suggest you begin thinking about what might happen if the guy is given the power he seeks.

The delusion that John Key is a hapless fool who’s somehow mysteriously gotten his hands on the reins of power remains very much alive within New Zealand lefties; this was the tired old line I got spun as recently as this afternoon, by one of the internet’s best-known Labourites (with a nice dollop of ‘if you don’t praise Labour, you’re a rightie’ for good measure).

But this tendency to misjudge and underestimate Key is only part of the problem. Denizens of The Standard aside, anyone within the loop who has a modicum of reason has figured out that Key is not the lightweight he was — quite willingly — framed as. But now the narrative is set: it’s That Nice Man John Key, who drinks beer out of the bottle while tending the barbecue with Prince Harry, and thinks Liz Hurley is hot. They don’t have a credible counter-narrative, but they have to say something against the health cuts, education cuts, tax cuts, ACC cuts, pending privatisation and so on — and so they fall back on their usual tired old cliches, which, while superficially looking like what an opposition is supposed to do, lack cohesion and run counter to the established wisdom about Key and his government — wisdom laid down, in the first place, by the Labour party in its 2008 campaign.

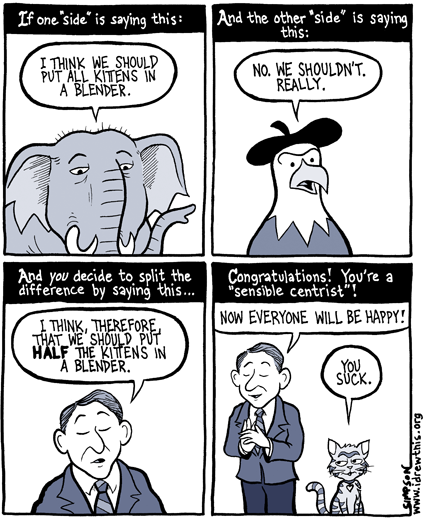

The lack of narrative cohesion is so dire that the party claims that privatisation of SOEs is repugnant to the voting public of New Zealand; and almost simultaneously puts out a press release saying that it’s a cynical ploy to “cling to power”. The manifest incompatibility of these two propositions — cynically promoting an unpopular policy to retain power — speaks for itself.

If the inability to construct a viable narrative is symptomatic of a wider lack of ideas and direction within Labour. Election-year spin aside, their policy offering is weak as well. Their big blockbuster kicking-off-election-year policy of a $5000 tax-free zone was big enough to draw plenty of criticism about cost and targeting (including from people like Brian Easton), but timid enough that nobody was made to sit up and take notice for any other reason (sidenote: when Brian Easton, John Shewan, Chris Trotter and I all oppose something, I think you can be pretty sure it’s not a winner).

This is just the most recent example of what we’ve seen throughout the past two years: Labour’s vision, and its execution, simply aren’t up to scratch. I have no internal knowledge of the Labour party, and I don’t know whose fault this is. I guess the leadership blames the strategists, the strategists blame the policy wonks, the policy wonks blame the spin-doctors and the spin-doctors blame the MSMâ„¢. All that’s just excuse-making for losers. There are no socially-just power-redistribution schemes in politics, and if there were they would be rorted. There is no fair. The job of being in opposition is to win despite the odds being stacked against you; to do and say things worthy of the news media’s time, worthy of the government’s concern, and worthy of the electorate’s endorsement. If you’re not doing that, you’re not up to the task.

As the title implies, the political weather this election year is not going to be a warm drizzle. John Key wants a mandate; he wants a strong and broad mandate which will permit him to wreak widespread social, economic and political changes upon New Zealand’s landscape, and he is prepared to put a lot on the line to gain it. He is playing for keeps, and my instinct is that an opposition who couldn’t keep pace with ‘smile and wave’ is going to be crushed by the rampant beast which is currently girding for war. What’s more, by all accounts Key is actually, genuinely coming to the New Zealand electorate with a transparent policy offering in good faith, keeping his promise that nothing would be privatised without his first having sought a mandate to do so, which robs Labour of their strongest symbolic weapon: the “by stealth” bit of their catchcry “privatisation by stealth”. Time will tell if this holds, but at present the Key government is doing exactly what it says on the box. Labour can’t claim they haven’t known about this all along. Privatisation has been the bogeyman about which they’ve been warning the New Zealand public for at least a decade, which makes the incoherence of their recent response all the more unforgivable. That National would consider running an election campaign on this cornerstone issue, loathed and feared by so many New Zealanders, is surprising. That they can expect to do so without trying to get their agenda through on the sly is shocking. That they reasonably expect to do all that and win is unthinkable. Let there be no doubt: if Key wins this election on these grounds, it is because Labour, by failing to adequately discharge their role as a competent opposition, have permitted him to do so.

Perhaps it is not too late. Perhaps Key has overplayed his hand; perhaps Goff has a secret weapon. Perhaps a young Turk is fixing to roll Goff and his cadres and make a break for it. I do not think any of these are likely. So it may be that the one good electoral thing to emerge from 2011 is a heavy and humbling loss which would see the Labour party reduced to a meagre husk. An exodus of the lively and creative thinkers of the party to another vehicle; or the enforced retirement of the deadwood responsible for the present state of affairs; or both would clear the way for a thoroughgoing rejuvenation of the movement’s principles and its praxis and its personnel. While it would be cold comfort to the generation of New Zealanders who will bear the brunt of the Key government’s second and third-term policies, it would be a crucial and long overdue lesson in political hubris, never to be forgotten, and infinitely preferable to another narrow loss and the moribund hope that next time it’ll be different.

L