John Key and David Cunliffe both spent much of the election campaign talking about the dreaded “things that New Zealanders really care about”. But Key, under direct attack, was much more disciplined about sticking to those things. The metacampaign, Dirty Politics, and the Dotcom Bomb were worth nothing more than haughty dismissal. At the time this seemed arrogant and ill-advised — how could he just shrug off such scandal? But he did. The National party ran an orthodox, modern campaign. They stuck to their guns amid all the madness, and the result was triumphant.

The poster child for this campaign was candidate Chris Bishop, who ran an old-fashioned shoe-leather campaign in the Labour stronghold of Hutt South and pushed the party’s strategic genius Trevor Mallard to within a few hundred votes of losing the seat he has held for 20 years. No stunts, no social media hype, no concern for the wittering about his being a former tobacco lobbyist, he just talked to the people and listened to the answers that came back.

But how did they know?

A few days before the election, Russell Brown was polled by Curia, and posted the questions. Russell noted that “these questions aren’t really geared towards firmly decided voters” — and this is key. They don’t presuppose a strong position, they’re simple and to the point, and they lead respondents through a narrative about what leadership is about and what government is for. And they seem as if they would yield an enormous amount of actionable data, not only about what voters value, but about why they value it. On election night, Key singled out Curia pollster David Farrar for particular praise:

“To the best pollster in New Zealand — and don’t charge us more for it — David Farrar, who got his numbers right! And who I rang night after night, even though I was told not to, just to check.”

John Key could afford to dismiss the metapolitics because he had plenty of good data telling him that people didn’t care about it, and to the extent that they did care about it, it favoured him. The single most evident difference between the campaigns is that When John Key said “the things New Zealanders really care about” he actually knew that these were the things that New Zealanders actually care about. The National party ran a reality-based campaign, not a hype-based, or a hope-based, or a faith-based campaign. In this they mirrored the most famous hope-based campaign of all time — Barack Obama’s — where the breezy, idealistic messaging was built on a rock-solid data foundation.

Key seems to have been the only party leader who was really secure in this knowledge. The Greens and Labour did seem to want to stick to their guns, but their data was evidently not as good, and they bought at least some of the hype that Dirty Politics and the Dotcom Bomb would bring Key low. So did I. But nothing much is riding on my out-of touch delusions. But opposition has a responsibility to be, if not reality-based, then at the very least reality-adjacent.

Play, or get off the field

I am a terrible bore on this topic. I have been criticising Labour, in particular, since at least 2007 on their unwillingness or inability to bring modern data-driven campaign and media strategy to bear in their campaigns — effectively, to embrace The Game and play it to win, rather than regarding it as a regrettable impediment to some pure and glorious ideological victory. Mostly the responses I get from the faithful fall under one or more of the following:

- National has inherent advantages because the evil old MSM is biased

- the polls are biased because landlines or something

- the inherent nature of modern neoliberal society is biased

- people have a cognitive bias towards the right’s messaging because Maslow

- it inevitably leads to populist pandering and the death of principle

- The Game itself devours the immortal soul of anyone who plays ( which forms a handy way to demonise anyone who does play)

But data is not a Ring of Power that puts its users in thrall to the Dark Lord. And, unlike the One Ring, it can’t be thrown into a volcano and the world saved from its pernicious influence. Evidence and strategy are here to stay. Use them, or you’re going to get used. The techniques available to David Farrar and the National party are not magic. They are available to anyone. Whether Labour has poor data or whether they use it poorly I do not know. It looks similar from the outside, and I have heard both from people who ought to know. But it doesn’t really matter. Data is only as good as what you do with it. Whatever they’re doing with it isn’t good enough.

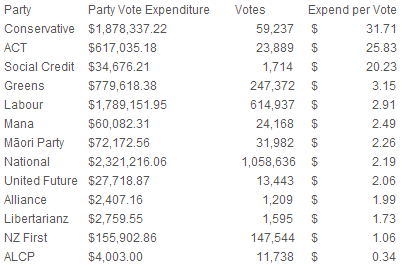

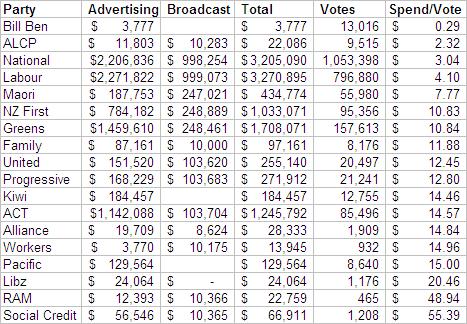

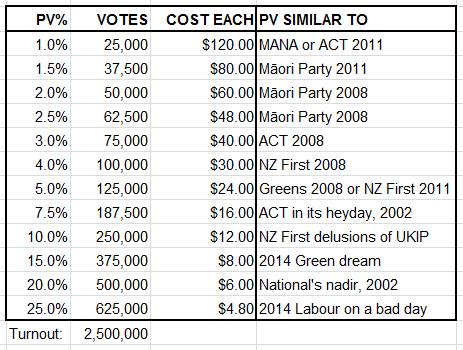

The best example from this campaign isn’t Labour, however — it’s Kim Dotcom. He said on election night that it was only in the past two weeks that he realised how tainted his brand was. He threw $4.5 million at the Internet MANA campaign and it polled less than the MÄori Party, who had the same number of incumbent candidates and a tiny fraction of the money and expertise. Had he thought to spend $30,000 on market research* asking questions like those asked by Curia about what New Zealanders think of Kim Dotcom, he could have saved himself the rest of the money, and saved Hone Harawira his seat, Laila Harré her political credibility, and the wider left a severe beating.

That is effective use of data: not asking questions to tell you what you want to hear, but to tell you what you need to know. This electoral bloodletting is an opportunity for the NZ political left to become reality-adjacent, and we can only hope they take it. Because if they don’t, reality is just going to keep winning.

L

* In response to this figure, UMR pollster Stephen Mills tweeted “$1000 would have been enough”.