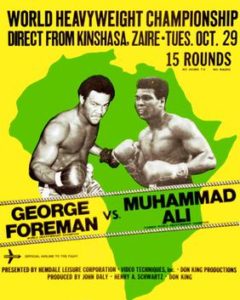

Older readers will remember the “Rumble in the Jungle” where Muhammad Ali defeated George Foreman for the heavyweight boxing title. Held in Kinshasa, Zaire in 1974, the contest pitted the undefeated champion Foreman, a beast of a man whose stock in trade was brutal early round knockouts of people such as Joe Frazier, Ken Norton and other contenders of the time (the uppercut punch that KO’d Norton earlier in 1974 actually lifted him off of the ground) against an ageing Ali, well past his prime after lengthy suspension when his concientious objection to the Vietnam War was ruled invalid and he was convicted of draft-dodging.

In the build up to the fight Ali pushed the line that he was going to take the fight to Foreman with his superior speed and agility. But Foreman and his trainers knew, based on the workouts Ali allowed the public and media to see, that his hand, head and foot speed were no longer what they used to be, and he could no longer “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.” The Foreman fight plan was therefore simple: bear down on Ali, cut off escape angles and corner him in the corners and on the ropes, then expose and exploit his slowness in a ferocious and relentless beatdown.

As readers will know, that did not happen. Ali privately trained to absorb body blows and using the lax rules of the boxing federations sponsoring the fight, was able to get the ring ropes loosened to their maximum extent (which allowed up to 12 inches of slack from the bottom to the top rope). Come fight time, this allowed Ali to lean back against the ropes, absorb Foreman’s increasingly frustrated and reckless body blows while dodging the occasional head shot and in doing so conserve energy by not punching himself out in a toe-to-toe brawl.

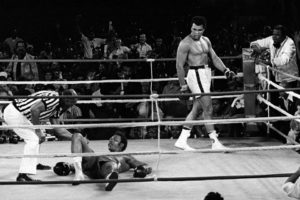

By the eighth round Foreman had thrown hundreds of punches. He was staggering around the ring in pursuit of Ali and physically spent, punch drunk and arm weary from throwing jabs, roundhouses and uppercuts rather than taking them. Once his hands dropped and stayed at his sides Ali pounced, using a series of jabs and hard rights to knock him down and out. It remains one of the greatest sporting upsets–and spectacles–of all time.

I mention this anecdote because it seems to me that we are witnessing a variation on this theme in US politics today. Although it is blasphemous to say so, think of Trump as Ali, his civil and political opposition and mainstream media as Foreman, the courts as the referee and the Republican party and rightwing corporate and social media, including state-sponsored trolls and disinformation purveyors, as the ropes.

In a straight up contest between Trump and the US constitutional system of checks and balances, it would be no contest. The courts, Congress and independent media would prevent Trump from slipping the boundaries of executive responsibility, would hold him to account and would punish him when he transgressed. Given his background and behaviour, he would not make it out of the first round.

But in the US today he has a support cushion in the GOP and rightwing media. Like the rules governing the tension on boxing ring ropes, the strictures governing partisan behaviour and truth in reporting have been stretched to their limits. Every blow he is dealt by the institutional system–the “swamp” as he calls it–is absorbed and countered by a chorus of hyper-partisan hyperbole and media ranting about “fake news,” conspiracies and the “Deep State.” This allows Trump to deflect, weave, dodge and counterpunch his accusers, questioning their character, motives, looks and heritage as if these were somehow equivalent or worse than the activities he has and is engaged in. The courts can only enforce what exists on paper, and since what exists on paper regarding presidential conduct is predominantly an issue of norms, custom and mores rather than legal accountability, there are limits to what they can do as referees in battles between Trump and other institutions.

Put another way: Normally a wayward president could not stand toe to toe with the institutional system of checks and balances without taking a beating. But that assumes that the limits of executive power are codified in law and not subject to manipulation. This turns out to be untrue. Much executive power does in fact answer to the law, at least in terms of how presidential decisions affect others. But much of it is also a product of precedent, practice, custom and tradition, not legislation, particularly when it comes to the president’s personal behaviour. In turn, the limits of presidential behaviour has always rested on the assumption that the incumbent will honour the informal traditions and responsibilities of office as well as the nature of the office itself, and not seek to manipulate the position for pecuniary and political self-advantage and/or personal revenge.

Trump has done exactly that. He regards the presidency as a personal vehicle and has disdain and contempt for its traditions and norms. He realises that he can play loose with the rules because the political constraints that bind him have been loosened by his corporate, congressional  and media supporters. He and his allies are willing to play dirty and use all of the tools at his disposal to thwart justice and destroy opponents.

This is the great irony of US politics. For a country that provides itself on constitutional protections and the “rule of law,” the framework governing presidential behaviour is little more than the ropes on a boxing ring.

For those interested in a return to civility and institutional norms this is problematic but is not the only thing that parallels the “rumble in the jungle.” Like Trump’s attacks on those investigating him in the FBI and Justice Department, for months prior to the fight Ali poisoned the well of good will towards Foreman. Ali lost his prime fighting years to the suspensions levied on him by boxing associations after he refused to be inducted into the US Army in 1967. Although he never spent time in jail and became an icon of the anti-War movement, he resented the five lost athletic years and those who profited by stepping into the ring during his absence. He particularly loathed Foreman, who he considered to be the white man’s favorite because of his quiet, polite and compliant demeanour out of the ring. He publicly labeled Foreman an “Uncle Tom” and “House Negro” who turned his back on his fellow people of color. Although none of this was verifiable, Ali’s charges resonated beyond boxing circles.

When Ali arrived in Kinsasha he held public training events that were part sparring, part evangelical preaching. He railed against colonialism and imperialism, averred his faith in Islam, lauded African nationalists like Mobuto Sese Seko, then-president of the host country Zaire (and not one known for his affinity for democratic rights), and generally carried on like a bare-chested revolutionary in shorts and gloves. Foreman, for his part, stayed quiet, trained mostly in private and had his handlers speak for him. When they entered the ring on that storied night, the 60,000 strong crowd crammed into the national stadium was overwhelmingly on Ali’s side.

Perhaps Ali’s mind games were designed to help sway the judge’s decision in the event that it was close. Perhaps it was to intimidate Foreman himself. Whatever the motive, there is a parallel to be drawn with Trump’s attacks on his critics and investigators on Twitter, at press conferences and at campaign-style rallies. His ranting serves to raise public suspicion about the critical media and federal law enforcement much in the way Ali’s insults about Foreman had the effect of raising questions about his ethnic identification and personal integrity, something that eventually turned African opinion against him. Could the same happen with Trump’s support base and undecided voters in the US?

It is too early to tell if Trump’s “rope a dope” political strategy will see him triumph over his adversaries. But that leaves pending an open question: is there a person out there that can play Leon Spinks to Trump’s Ali? And if so, is that person named Robert Mueller, or could it turn out to be Stormy Daniels?

One thing is certain. Trump is a big fan of the WWE and likes to fancy himself as a tough guy willing to take on all challengers. However, in this contest, unlike the WWE, the outcome is not pre-determined and the blows are both real and far from over.