One thing I used to do early in undergraduate classes is to ask students if humans were inherently more conflictual or cooperative. I noted that all primates and many other animal species had both traits, but that humans were particularly elaborate in their approach to each. I also noted that the highest form of human cooperation is war, where large numbers of humans cooperate in complicated maneuvers that combine lethal and non-lethal technologies over time and distance with the purpose of killing each other.

It was interesting to observe the gender and nationality differences in the response. Males tended to see things as being more conflictual while female students (again, these were 18-22 year olds) tended to see things in a more cooperative light. US students tended to see things  as being more conflictual than kiwi students, although it was also interesting to note the differences between political science majors (who saw things as being mostly conflictual, although here too there were differences between international relations, comparative politics and political theory majors) and those majoring in other disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, history, philosophy and fine arts types (I tended to not pay much attention to the opinions of medical students or hard science majors like chemistry or physics students, much less engineering students, simply because these people were pursuing distributional requirements and therefore not that interested in the subject of the courses that I teach, and tend to dwell less on the moral and ethical dilemmas inherent in human existence and more on solving practical  problems much as plumbers do–this includes the pre-med and med students I encountered over 25 years of teaching, which says something about the character of those who want to be medical doctors in all of the countries in which I have taught).

Singaporean students exhibit strong gender differences along the lines described above and reinforce everything else I have seen before when it comes to this question. In spite of the constant push by the PAP-dominated State to emphasize racial and cultural harmony, the majority of students I have encountered in 3 years of tutoring and teaching in SG see things as being mostly conflict-driven (with some interesting ethnic dispositions in that regard as well). For all of its official preaching of harmony, SG is very much a conflict-driven place.

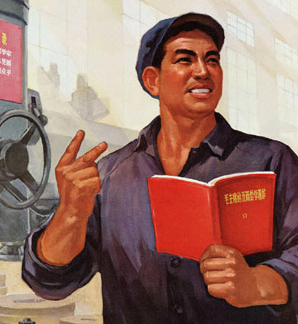

I used my own experience to show how one trait or another can be reinforced via socialisation. Coming out of Argentina in the early 1970s  I viewed politics as class war by other means. It was all-out conflict and I was socialised to see it as such and behave accordingly. For the Argentine elite “communists” and other challengers to the status quo had to be eradicated–and often were. For Left militants the imperialist enemy and its local lackeys had to be annihilated if ever Argentina was to be a fair and just country. Needless to say, when I arrived in the US to begin my university studies with this zero-sum view of politics, my undergraduate peers thought that I was nuts–this, even though it was the Nixon/Agnew era and I had all sorts of ideas about how these clear enemies of the world’s working classes could be assisted on the journey to their deserved places in Hell.

Instead, my undergraduate friends preferred the shared comforts of bongs, beers and each other (this was the age before AIDS so such comforts could be pursued in combination in a relatively unfettered manner). They preferred cooperation to conflict, and after unsuccessfully trying to convert a few of them to my more contentious view of life, I decided that When In Rome (before the Fall)…..you get the picture (although I never did quite give up the view that politics is essentially war by other means, something undoubtably reinforced by my ongoing engagement with Latin America as an academic and US security official).

If one thinks of the difference between Serbs and Swedes, or Afghans and Andorrans, one sees that a major point of difference is the cultural predisposition to conflict or cooperate. Be it individuals, groups or the society as a whole, the tendency to be cooperative or conflictual rests on the relative benefits accrued from either, reinforced over time by custom, practice and experience until it becomes an indelible feature of the social landscape passed on from family to family and generation to generation.

Within otherwise stable societies some social groups are more or less disposed to conflict or cooperation than others. This is not necessarily reducible to class status. Although their social graces may be more refined and the veneer of cooperation makes them appear to be more “civilised,” the rich may be just as prone to conflict as are the poor. Conversely, the working class, when self-conscious and organised, is quite capable of undertaking mass cooperation in pursuit of common goals even if some actions, such as strikes, are clearly conflictual in nature (which again goes back to my adolescent notion that economics as well as politics in a class system are essentially war substitutes given distributional conflict over a limited or finite amount of socially-allocated resources).

One might argue that the advent of market-driven social philosophies, with their common belief that all individuals and groups are self-interested maximizer’s of opportunities, pushed the replacement of cooperative approaches towards the common good with hyper-individualistic, conflictual approaches in what amounts to a feral perspective on the social order. The latter exist in many lesser-developed societies in which pre-modern tensions and capitalist wealth generation create the conditions for abject greed, corruption and despotism. The twist to the tale is that in the advanced liberal democratic capitalist world, the turn to market steerage also appears to have brought with it a turn away from social cooperation and towards social conflict. Â Now the tendency towards conflict appears to be the norm rather than the exception and it is no longer social reprobates and sociopaths who engage in conflictual approaches towards inter-personal or inter-group disagreement or dispute resolution.

Which brings up the questions: has NZ followed this sad trajectory in recent years? Has it always been more cooperative than conflictual as a a societal disposition, or is that just a myth that belies that reality of a society with a historical disposition to be in conflict with itself in spite of its peaceful international reputation?

I leave it for the readers to ponder the basic premise as well as the true nature of NZ society then and now.