The last episode of season 3 of “A View from Afar” aired yesterday. It discusses the concept of hostage diplomacy and how it applies to the recent US-Russia prisoner exchange as well as the collective punishment involved in the Russian’s holding of Ukrainian cities hostage, and a few other things. In short: it is all about creating negotiating space and opening backdoor channels via the use of coercive diplomacy as leverage.

On NZ foreign policy “independence.”

For many years New Zealand elites have claimed to have an “independent” foreign policy, so much so that it has become a truism of NZ politics that transcends the partisan divide in parliament and is a shibboleth of the NZ foreign policy establishment that is parroted by media and pundits alike. But is it a correct characterization? More broadly, is any country able to maintain a truly independent foreign policy?

If “independence” in foreign policy is defined as the unfettered freedom and ability to pursue courses of action in the international arena without regard to cost or consequence, then the answer is no. Foreign policy independence is an aspirational goal (for some) rather than a practicable achievement (for very few).

Instead, what NZ has is a flexible foreign policy based on what can be called constrained or bounded autonomy. Just like the notion of bounded rationality in game theory (where rationality is not opened-ended but framed by the interactive context in which decisions are made), NZ’s foreign policy autonomy occurs within identifiable parameters or frameworks governing specific international subjects and relationships that are not fungible or identical in all instances. Some are broad and some are limited in scope. Some are more restrictive and some are looser in application. Some are more issue-specific or detailed than others depending on the frameworks governing them. Within those parameters NZ has a significant range of foreign policy-making choice and hence room to maneuver on the world stage.

One reason that NZ does not have an independent foreign policy is that NZ is inserted in a latticework of formal and informal international networks and relationships that to varying degrees constrain its behavior. Things like membership in TPPA, 5 Eyes, WTO, IMF, WHO, NPT, COP, World Bank, INTERPOL and other multinational agencies as well as regional organizations like the Pacific Island Forum, Five Powers Agreement, NATO partnership and various international conservation and legal regimes, as well as bilateral agreements such as the NZ-PRC FTA, Washington and Wellington Agreements and Australia-NZ close defense relations, clearly demonstrate that NZ has formal and informal commitments that bring with them (even if self-binding) responsibilities as well as opportunities and privileges. What they do not bring and in fact mitigate against is foreign policy independence.

This latticework of relationships is the foundation for NZ’s commitment to a rules and norms-based international order because as a small country operating in a world dominated by great and medium powers, it is the commitment and enforcement of international codes of conduct that balances the relationships between big and small States. That gives NZ a measure of institutional certainty in its foreign relations, something that consequently grants it a degree of autonomy when it comes to foreign policy decision-making.

This is what allows NZ, in the broader sense of the term, to be flexible in its foreign policy. Within its broadly autonomous and flexible position within an international system governed by an overlapping network of rules, regulations and laws, comes the “nested” (as in “nested “ games as per rational choice theory, where the broadest macro-game encompasses a series of “nested” meso- and micro-games) ability to move between approaches to specific issues in a variety of areas in the diplomatic, economic and security spheres.

A second reason that NZ does not have an independent foreign policy is due to what international relations theorists call the “Second Image” effect: the influence of domestic actors, processes and mores on foreign policy-making. NZ’s foreign policy is heavily dominated by trade concerns, which follow mercantilist, Ricardian notions of comparative and now competitive advantage. The logic of trade permeates NZ economic thinking and has a disproportionate influence on NZ foreign policy making, at times leading to contradictions between its trade relations and its support for liberal democratic values such human rights and democracy. As trade came to dominate NZ foreign policy it had a decided impact at home, with the percentage of GDP derived from import-export trade averaging above 50 percent for over three decades (with a third of the total since 2009 involving PRC-NZ trade).

Meanwhile, the domestic ripple effect of trade-related services expanded rapidly into related industries (e.g., accounting, legal and retail services related to agricultural export production), adding to its centrality for national economic well-being. As things stand, if NZ was to be cut off from its major trading partners (the PRC and Australia in particular), the economic shock wave would wash over every part of the country with devastating consequences.

What this means in practice is that export sector interests have a disproportionate influence on NZ’s foreign policy-making. The country’s material dependence on trade in turn locks in pro-trade mindsets amongst economic and political elites that either subordinate or inhibit consideration of alternative priorities. That reduces the freedom of action available to foreign policy-makers, which reduces their independence when it comes to formulating and implementing foreign policy in general. Almost everything passes through the filter of trade, and questions about trade are dominated by a narrative propagated by actors with a vested interest in maintaining the trade-dependent status quo.

Althugh less influential than the export-import sector, other domestic actors also place limits on foreign policy independence. Disapora communities, the intelligence and military services, tourism interests, religious groups, civil society organizations—all of these work to influence NZ’s foreign policy perspective and approaches. Balancing these often competing interests is an art form of its own, but the key take-away is that the influence of domestic actors makes it impossible for NZ to have a truly “independent” foreign policy for that reason alone, much less when added to the international conditions and frameworks that NZ is subject to.

Given those restrictions, the key to sustaining foreign policy flexibility lies in being principled when possible, pragmatic when necessary and agile in application. Foreign policy should be consistent and not be contradictory in its implementation and requires being foresighted and proactive as much as possible rather than short-sighted and reactive when it comes to institutional perspective. Crisis management will always be part of the mix, but if potential crises can be foreseen and contingency scenarios gamed out, then when the moment of crisis arrives the foreign policy-making apparatus will better prepared to respond agilely and flexibly.

In short, NZ has and should maintain a flexible foreign policy grounded in support for multilateral norms and institutions that allows for autonomous formulation and agile implementation of discrete positions and approaches to its international relations and foreign affairs. Whether it can do so given the dominance of trade logics in the foreign policy establishment remains to be see.

The big picture.

The issue of foreign policy independence matters because the world is well into the transition from unipolarity (with the US as the hegemon) to multipolarity (which is as of yet undefined but will include the PRC, India and the US in what will eventually be a five to seven power constellation if the likes of Japan, Germany and other States emerge to prominence). Multipolar systems are generally believed to be more stable than unipolar systems because great powers balance each other on specific issues and obtain majority consensus on others, which avoids the diplomatic, economic and military bullying (and response) often associated with unipolar “hegemonic” powers. However, the transition from one international system to another is marked by competition between rising and declining great powers, with the latter prone to starting wars in a final ttempt to save their positions in the international stats quo.

In the period of long transition and systemic realignment uncertainty is the new normal and conflict becomes the default systems regulator because norm erosion and rules violations increase as the old status quo is challenged and the new status quo has yet to be consolidated. This leads to a lack of norm enforcement capacity on the part of international organizations rooted in the old status quo, which in turn invites transgressions based on perceived impunity by those who would seek to upend it. This has been seen in places like the South China Sea, Syria, and most recently Ukraine.

The transitional moment is also marked by conflicts over the re-defining of new rules of systemic order. These conflicts may or may not lead to war, but the overall trend is the replacement of the old system (unipolar in the last instance) with something new. Illustrative of this is the Russian invasion of Ukraine, where a former superpower well into terminal decline has resorted to war on a smaller neighbor as a last attempt to hold on to Great Power status. No matter what the outcome of the conflict itself, Russia will be much diminished by its misadventure and therefore will not be a member of the emerging multipolar configuration.

The new multipolar order will include traditional “hard” and “soft” power usage but will also include “smart” and “sharp” power projection (“smart” being hybrids of hard and soft power and “sharp” being a directed focus by State actors on achieving specific objectives in foreign States via directed domestic influence and hybrid warfare campaigns in those States).

They core feature of the emerging multipolar system is balancing. Great Powers will seek to balance each other on specific matters, leading to temporary alliances and tactical shifts depending on the issues involved. They will then seek the support of smaller States, creating alliance constellations around individual or multilateral positions.That is why systemic multipolarity is best served when odd numbers of Great Powers are present in the configuration, as this allows for tie-breaking on specific subjects, to include rules and norms re-establishment or consolidation.

More importantly, in multipolar systems balancing becomes both a focus and a feature of State behaviour (i.e. States seek to balance each other on specific issues but also desire to achieve an overall balanced system of interests in the multipolar world). In a sense, multipolar balancing is the diplomatic equivalent of the invisible hand of the market: all actors may wish to pursue their own interests and influence the system in their favour, but it is the aggregate of their actions that leads to systemic equilibrium and international market clearing.

In a nutshell: although international norms violations are common and conflict becomes the default systems regulator during periods of international transition and systemic realignment, the multipolar constellation that emerges in its wake is chracterised by balancing as both a focus and a feature. That demands flexibility and agility on the part of great powers but also gives diplomatic space and opportunity to smaller powers with such traits.

In this context a flexible and agile foreign policy approach allows a small State such as NZ considerable room for maneuver, may magnify its voice regarding specific areas of concern (such as climate change, environmental security, migration and the general subject of human rights, including indigenous and gender rights) and therefore give it increased influence disproportionate to its size and geopolitical significance (in other words, allow it to genuinely “punch above its weight”).

Issues for New Zealand.

On the emerging international system.

If a flexible and agile foreign policy is pursued, NZ has the ability to expand its diplomatic influence and range of meaningful choice in the emerging system. For self-interested reasons, NZ must push for the early consolidation of a new multipolar order dominated by liberal democracies, recognizing that there will be authoritarian actors in the arrangement but understanding that a rules-based international order requires the dominance of liberal democratic values (however hypocritically applied at times and always balanced by pragmatism) rather than authoritarian conceptualisations of the proper world order. In practice this means extending the concept of “liberalism” to include non-Western notions of cooperation, consensus-building, transparency and proportional equality of participation and outcomes (this is seen in the current NZ government’s inclusion of “Maori Values” in its policy-making orientation). The need for univerally binding international rules and norms is due to the fact that they help remove or diminish power asymetries and imbalances that favor Great Powers and therefore level the playing field when it comes to matters of economic, cultural, diplomatic and security import. For this reason and because it is a small State, NZ has both a practical reason to support a rules-based international order as well as a principled one.

NZ and the PRC-US rivalry.

The key to navigating US-PRC tensions is to understand that NZ must avoid the “Melian” Dilemma:” i.e., being caught in the middle of a Great Power conflict (the phrase comes from the plight of the island-state Melos during the Peloponnesian Wars, where Melos attempted to remain neutral. Sparta agreed to that but Athens did not and invaded Melos, killed its men, enslaved women and children and salted its earth. The moral of the story is that sometimes trying to remain neutral in a bigger conflict is a losing proposition).

NZ will not have a choice as to who to side with should “push come to shove” between the US and PRC (and their allies) in a Great Power conflict. That choice will ultimately be made for NZ by the contending Powers themselves. In fact, in a significant sense the choice has already been made: NZ has publicly stated that it will stand committed to liberal international values, US-led Western security commitments and in opposition to authoritarianism at home and abroad. While made autonomously, the choice has not been made independently. It has been forced by PRC behaviour (including influence, intimidation and espionage campaigns in NZ as well as broader misbehavior such as its record of intellectual property theft, cyber-hacking and the island-building projects in the South China Sea) rather than NZ’s desire to make a point. Forced to preemptively choose, it is a choice that is principled, pragmatic if not necessarily agile in application.

How much to spend on defense?

Focus on overall Defense spending (however measured, most often as percentage of GDP) is misguided. What matters is not how much is spent but how money is spent. Canada, for example, spends less (1.3 percent) of GDP than NZ does (1.6 percent) even though it a NATO member with a full range of combat capabilities on air, land and sea. The 2 percent of GDP figure often mentioned by security commentators is no more than a US demand of NATO members that is most often honoured in the breach. Although it is true that Australians complain that NZ rides on their coattails when it comes to defense capabilities, NZ does not have to follow Australia’s decision to become the US sheriff in the Southern Hemisphere and spend over 2.5 percent/GDP on defense. Nor does it have the strategic mineral resource export tax revenues to do so. Moreover, even if it overlaps in places, NZ’s threat environment is not identical to that of Autsralia. Defense priorities cannot be the same by virtue of that fact, which in turn is reflected in how the NZDF is organized, equipped and funded.

NZ needs to do is re-think the distribution of its defense appropriations. It is a maritime nation with a land-centric defense force and limited air and sea power projection capabilities. It spends the bulk of its money on supporting this Army-dominant configuration even though the Long-Term Issue Brief recently issued by the government shows that the NZ public are more concerned about non-traditional “hybrid” threats such as disinformation, foreign influence operations (both State and non-state, ideologically-driven or not), climate change and natural disasters as well as organized crime, espionage and terrorism. More pointedly, the NZDF has a serious recruitment and retention problem at all staffing levels, so no material upgrades to the force can compensate for the lack of people to operate equipment and weapons.

This is not to say that spending on security should completely shift towards non-traditional, non-kinetic concerns, but does give pause to re-consider Defense spending priorities in light of the threat environment in which NZ is located and the political realities of being a liberal democratic State where public attention is focused more on internal rather than external security even if the latter remains a priority concern of security and political elites (for example, with regard to sea lanes of communication in the SW Pacific and beyond). That leads into the following:

Trade.

Trade is an integral component of a nation’s foreign policy, particularly so for a country that is unable to autonomously meet the needs and wants of a early 21st consumer-capitalist society. The usual issue in play when it comes to foreign trade is whether, when or where trade relations with other countries should directly involve the State, and what character should such involvement adopt. Should it be limited to the imposition of tariffs and taxes on private sector export/imports? Should it be direct in the form of investment regulations, export/import controls, and even State involvement in negotiations with other States and private commercial interests? Should the overall trade orientation be towards comparative or competitive value? Most of these questions have been resolved well in NZ, where the government takes a proactive role in promoting private sector NZ export business but has a limited role beyond that other than in regulatory enforcement and taxation.

One change that might help erode NZ foreign policy subordination to trade-focused priorities is to either separate the Trade portfolio from the Foreign Affairs Ministry or to create a Secretariat of Trade within Foreign Affairs. In the first instance “traditional” diplomacy can be conducted in parallel to trade relations, with consultative working groups reconciling their approaches at policy intersection points or critical junctures. In the second instance Trade would be subordinated to the overarching logic of NZ foreign affairs and act as a distinct foreign policy component much like regional and subject-specific branches do now. The intent is to reduce foreign policy dependence on trade logics and thereby better balance trade with other diplomatic priorities.

The larger issue that is less often considered is that of “issue linkage.” Issue linkage refers to tying different threads of foreign policy together, most often those of trade and security. During the Cold War trade and security were closely related by choice: security partners on both sides of the East-West ideological divided traded preferentially with each other, thereby solidifying the bonds of trust and respect between them while benefitting materially and physically from the two dimensional relationship. NZ was one of the first Western countries to break with that tradition, and with its bilateral FTA with the PRC it completely divorced, at least on paper, its trade from its security. That may or may not have been a wise idea.

In wake of events over the last decade, NZ needs to reconsider its position on issue linkage.

Issue linkage does not have to be bilateral and does not have to involve just trade and security. Here again flexibility and agility come into play across multiple economic, diplomatic and military-security dimensions. For example, NZ prides itself on defending human rights and democracy world-wide. However, in practice it has readily embraced trade relations with a number of dictatorial regimes including the PRC, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Iran, and Singapore (which whatever its veneer of electoral civility remains a one party-dominant authoritarian State). It also provides developmental aid and financial assistance to nobility-ruled countries like Samoa and Tonga. The question is how to reconcile these relationships with the professed championing of democracy and human rights

It is not an easy question to answer and is where the “pragmatic when necessary” perspective clashes with the “principled when possible” approach. It might be the case that human rights and democracy can (some might say should) not be linked to trade. But that would mean ignoring abuses of worker’s rights and other violations like child labour exploitation in trading partners. It is therefore a complicated dilemma that might best be resolved via NZ support for and use of multinational organizations (like the ILO and WTO ) to push for adherence to international standards in any trade pact that it signs.

A potentially more fruitful linkage might be between climate change mitigation measures and sustainable production and trading practices. Each trade negotiation could include provisions about carbon reductions and other prophylactic measures throughout the production cycle, where sharing NZ’s acknowledged expertise in agricultural emissions control and other environmental conserving technologies can become part of NZ’s negotiating package.

Alternatively, in the emerging post-pandemic system of trade a move to replace “off-shoring” of commodity production with “near-shoring” and even “friend-shoring” has acquired momentum. Near-shoring refers to locating production centers closer to home markets, while friend-shoring refers to trading with and investing in countries that share the same values when it comes to upholding trade and after-entry standards, if not human rights and democracy. Combining the post-pandemic need to de-concentrate commodity production and create a broader network of regional production hubs that can overcome the supply chain problems and negative ripple effects associated with the pandemic shutdown of production in the PRC, NZ could engage in what are known as mini-lateral and micro-lateral initiatives involving a small number of like-minded regional partners with reciprocal trading interests.

Australia and the Pacific.

Rather than get into specifics, here a broad appraisal is offered.

Australia is NZ’s most important international partner and in many aspects very similar to it. However, beyond the common British colonial legacy and shared Anglophone war experiences they are very different countries when it comes to culture, economy and military-diplomatic outlook. Likewise, NZ shares many traits with other Pacific island nations, including the seafaring traditions of its indigenus peoples, but is demonstrably distinct in its contemporary manifestation. More broadly, Austalia acts as the big brother on the regional block, NZ acts a middle sister and the smaller island States act as younger siblings with their own preferences, attitudes and dispositions.

To be clear: the family-like characterisation is a recognition of the hierarchical yet interdependent nature of the relationships between these States, nothing more. For NZ, these relationships represent the most proximate and therefore most immediate foreign policy concerns. In particular, the English speaking polynesian world is tied particularly closely to NZ via dispora communities, which in many cases involves NZ-based islanders sending remmitances and goods to family and friends back home. Island nations like Samoa and Tonga are also major recipients of NZ developmental aid and along with the Cook Islands are significant tourist destinations for New Zealanders.

Because of their extensive trade relationship and long-standing diplomatic and military ties, NZ understands that maintaining warm relations with Australia is vital to its national interests.

Where it can differentiate itself is in its domestic politics, offering a more inclusive and gentler form of liberal democratic competition that avoids the harder edged style displayed by its neighbor. It can include a different approach to immigration, refugee policy, indigenous rights, and the role of lobbyists and foreign influence in domestic politics, especially when it comes to political finance issues. Without being maudlin, NZ can be a “kinder, gentler” version of liberal democracy when compared to Australia, something that allows it to continue to work closely with its Antipodean partner on a range of mutal interests.

The key to maintaining the relationship with Austalia is to quibble on the margins of bilateral policy while avoiding touching “the essential” of the relationship.For example, disputes about the expulsion of Kiwi-born “501” criminal deportees from Australia to NZ can be managed without turning into a diplomatic rift. Conversely, combating foreign influence campaigns on local politics can be closely coordinated without extensive diplomatic negotiation in order to improve the use of preventative measures on both sides of the Tasman Sea.

The key to maintaining good relations with Pacific Island states is to avoid indulging in post-colonial condescension when it comes to their domestic and international affairs. If NZ truly believes in self-determination and non-interference in domestic affairs, then it must hoor that belief in practice as well as rhetorically. Yet, there has been a tendency by NZ and Australia to “talk down” at their Pacific neighbors, presuming to know what is best for them. There are genuine concerns about corruption in the Pacific community and the increased PRC presence in it, which is believed to use checkbook and debt diplomacy as well as bribery to influence Pacific Island state leaders in a pro-Chinese direction. But the traditionally paternalistic approach by the Antipodean neighbors to their smaller brethern is a source of resentment and has backfired when it comes to contanining PRC expansion in the Southwestern Pacific. The reaction to the recently announced Solomon Islands-PRC bilateral security agreement is evidence of that heavy-handedness and has been met with hostility in the Solomons as well as other island States at a time when the regional geopolitical balance is in flux.

To be sure, NZ offers much developmental aid and humanitarian assistance to its island neighbors and is largely viewed with friendly eyes in the region. The best of way of assuring that goodwill is maintained is to speak to island States as equals rather than subordinates and to emphasize the notion of a Pacific community with shared traditions, cultures and values. It is for the Pacific Island states to determine what their individual and collective future holds, and NZ must respect that fact even while trying to promote principles of democracy, human rights and transparency in government region-wide.

Summary.

It is mistaken and counter-productive to label New Zealand’s foreign policy as “independent.” A cursory examination of domestic and international factors clearly demonstrates why it is not. Instead, NZ purses a flexible foreign policy grounded in constrained or limited autonomy when it comes to foreign policy-making and which is operationalized based on agility when it comes to reconciling relationships with other (particularly Great) powers and manuevering between specific subjects. It is soft and smart power reliant, multilateral in orientation and predominantly trade-focussed in scope. It champions ideals tied to Western liberal values such as human rights, democracy, transparency and adherence to a rules based international order that are tempered by an (often cynical) pragmatic assessment of how the national interest, or least those of the foreign policy elites, are served.

Balancing idealism and pragmatism in non-contradictory or hypocritical ways lies at the core of NZ’s foreign policy dilemmas, and on that score the record is very much mixed.

This essay began as notes for a panel discussion hosted by https://www.theinkling.org.nz at the Auckland War Museum, November 3, 2022. My thanks to Alex Penk for inviting me to participate.

Media Link: The Era of Restive Politics.

In the latest “A View from Afar” podcast Selwyn Manning and I explore what can be called the era of restive politics in national and international affairs. We review recent political dynamics in the US, UK, Brazil, Italy, Iran and the PRC to highlight that in the post-pandemic world, public disgruntlement, resentment and frustration has less to do with ideology and more to do with governments failing to deliver on, much less manage popular expectations of what the State should provide to the polity. The issue is one of competence and responsiveness rather than ideological predilection.

This is true for authoritarian regimes as well as liberal democracies (hence the choice of a small-N “most different” comparative survey of case studies), but the remedies are all too often offered by populist demagogues who see political opportunity in the restive moment. You can find the podcast here.

Systemic Realignment and the Long Transition.

The last few decades have seen a world in increasing turmoil. Technological advances, climate deterioration, sharpening domestic and international political conflict and global pandemics are just some of the hallmarks of the contemporary world moment. In this essay I hope to outline some of the dynamics of this time by conceptually framing its recent historical underpinnings.

Think of international relations as a complex system. Because it involves living creatures (humans), rather than inanimate objects, we can think of it as an ecosystem made up of people and their institutions, norms, rules and the behaviours (confirmative or transgressive) that flow from them. The world order is comprised of various subsystems, including regional (meso) and national (micro) systems that encompass economic, political/diplomatic and socio-cultural features linked to but distinct from the global (macro) system.They key is to understand international relations and world politics as a malleable human enterprise.

International systems are dynamic, not static. Although they may enjoy long periods of relative stability or stasis, they are fluid in nature and therefore prone to change over time. In the last century stable world order cycles have become shorter and transitional cycles have become longer due to a number of factors, including technological advances in areas such as transportation and telecommunications, demographic shifts, the globalisation of production, consumption and exchange, ideological diffusion, cultural transfer and increased permeability of national borders. Status quos are more short-lived and transitional moments–moments leading to systemic realignment–are decades in length.

We are currently in the midst of such a long transitional moment.

In fact, the post-Cold War era is a period of long transition. After the fall of the USSR in 1990, the international order moved away from a tight bi-polar system where two nuclear-armed superpowers and their respective alliance systems deterred and balanced each other through credible counter-force based on second-strike capabilities in the event of strategic nuclear war. The bipolar alliance systems were “tight” in the dual sense that their diplomatic and military perspectives were closely bound to those of their respective superpowers (think NATO and the Warsaw Pact), and States in each security bloc tended to trade preferentially with each other (known as trade and security issue linkage).

The geopolitical map of the Cold War was divided into shatter and peripheral zones, with the former being places where direct superpower confrontation was probable and therefore to be avoided (such as Central Europe and East Asia), and the latter being places where the probability of escalation was low and therefore conflicts could be “managed” at the sub-nuclear level because no existential threats to the superpowers were involved (SE Asia, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and the South Pacific come to mind). Here proxy wars, guerrilla conflicts and direct superpower interventions could flourish as trialing grounds for great power weaponry and ideological supremacy, but the nature of the conflicts were opportunistic or expedient, not existential for the superpowers and their major allies. Escalation was dangerous in shatter zones; escalation was limited in the periphery.

With the demise of the USSR the bipolar world was replaced by a unipolar world where the US was the sole superpower and therefore considered the “hegemon” (in international relations jargon) where its economic, military and political power was unmatched by any one country or group of countries. This is noteworthy because “hegemonic” superpowers intervene in the international system for systemic reasons. That is, they approach the international system in ways that preserve an institutional and regulatory status quo that supports and reaffirms their position of dominance. In contrast, great and middle powers intervene in the international system in order to pursue national interests rather than systemic values. Absent a hegemon to act as systems regulator, this may or may not lead to disorder.

The hegemonic premise is the conceptual foundation of the liberal international foreign policy approach adopted by US administration and many of its allies (including NZ) during the post -Cold War period and which persists to this day. For the West, the combination of market economics and liberal democracy is the preferred political-economic form because it is seen as the best way to achieve peace and prosperity for its subjects. As a result, it needs to be expanded globally and supported by a “rules-based” international institutional order crafted in its image. Although this belief was honoured most often in the breach (as any number of US-backed military coups d’état demonstrate), it constituted the ideological foundation for post-Cold War international relations because there was no global alternative to it.

US dominance as the sole superpower and global “hegemon” lasted little more than a decade. After the 9/11 attacks (which were not, in spite of their horrifying spectacle, an existential threat to the US unless it over-reacted), the US engaged in a series of military adventures under the umbrella justification of fighting the (sic) “war on terror.” In doing so it engaged in what may be called neo-imperial hubris, which in turn led to neo-imperial overreach. By invading Iraq and extending the (arguably legitimate) original irregular warfare mission against the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan into an open-ended nation-building exercise, then invading Iraq on a pretext that it was involved in the 9/11 plot while conducting counter-terrorism operations in the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia and even in the wider European Rim, the US expended vast amounts of blood and treasure in pursuit of the unachievable goal of redrawing the map of the Middle East in an US-centred image.

That is because although terrorists can be physically eliminated, the ideas that propel them cannot, and unless there is an ideological project that can counter the ideological beliefs of the “extremists,” then the physical wars are a short-term solution to a long-term problem. The US (and the West in general) lacked an ideological counter to Wahabism and Salafism, so the roots of Islamic extremism remain even if its human materiel has been depleted. In addition, pursuing a war of opportunity (rather than of necessity) in Iraq only generated concern and resentment in the Arab world and laid the foundations of the emergence of ISIS as an irregular Sunni fighting force, prompted Iran to pursue its nuclear deterrence option, and diverted resources from the fight in Afghanistan. That in turn allowed the latter to turn into a tar baby for the ISAF coalition fighting the Taliban and various Sunni irregular groups, which eventually produced the graveyard of Empire scenes at Kabul and Bagram airports in 2022.

More importantly for our purposes, despite its surface appearances and the claims of some scholars that a unipolar international hierarchy is the most stable systemic arrangement, a unipolar world is inherently an unstable world. As the hegemon attempts to maintain its dominance in the international order by engaging in wars of conquest, military interventions in peripheral areas or by attempting to be the world’s “policeman” in parallel with economic and diplomatic efforts across the globe, it expends its power on several dimensions. At the same time, pretenders to the throne build their power while avoiding direct confrontations with the superpower until the balance shifts in their favour and the time becomes ripe for a challenge. That is the time when the knives come out. That time could well have arrived and the moment of long transition may be coming to a head.

The move from a unipolar to a multipolar world still in the making began on 9/11 and continues to this day. There is good and bad news in this transition. The good news is that multipolar systems characterised by competition and cooperation among a small odd number (3-7) of great powers is arguably the most stable of international orders because it allows each State to form alliances on specific issues and balance or counter-balance the ambitions of others. The preferred configuration is an odd number because that avoids deadlocks and facilitates cross-cutting alliance formation on specific issues. This leads to a situation where balancing becomes a primary feature and objective of the international system as a whole. In a sense, it is the geopolitical equivalent of the invisible hand of the market: actors act in pursuit of their preferred interests and with a desire to secure preferred outcomes, but it is the aggregate of their actions that leads to balancing and realignment. Actors may wish to steer outcomes in their favour but what eventuates is seldom in line with their individual preferences. Instead, multipolar “market” clearance rests on a dynamic balance of great power national interests..

The bad news is that in the period of transition between unipolar and multipolar orders, consensus on the rules governing State behaviour and adherence to institutional edicts and mores breaks down. International norm erosion becomes widespread, uncertainty becomes generalised and conflict becomes the systems regulator. A lack of enforcement capability by international organisations and States themselves allows norm violations to proceed unchecked and perpetrators to act with impunity (as see, for example, in Syria, the South China Sea or the Ukraine). While geopolitical shatter and peripheral zones continue to exist (albeit not as they existed during the Cold War), the majority of the world becomes contested space in which State, multinational and non-state actors vie for influence using a mix of power variables (say, for instance, chequebook and debt diplomacy, direct influence operations or trade and security agreements). This includes cyber- and outer space, which are increasingly at the forefront of hostile great power contestation.

In a sense, the transitional moment marks a return to a Hobbesian “state of nature” where, absent a Leviathan (the hegemonic power), States and non-state international actors use their power to achieve self-interested goals rather than communitarian ideals.

Transitional conflicts may be economic, cultural, political, military or some combination thereof. In the present moment conflicts are increasingly hybrid in nature, with mixes of persuasive and dissuasive (using mixtures of soft, hard, smart and sharp) power operating on multiple dimensions that, due to technological advancements, do not respect national sovereignty. States and non-state actors now appeal to and influence the predilections of foreign audiences in direct ways that might be called “intermestic” or “glocalized:” what is foreign is also domestic, what is local is global. For hostile actors, the objective of hybrid warfare campaigns that use direct influence tactics is to undermine the enemy from within rather than attack it from without.

There is little governmental filter or defence against such penetrations (say, on social media) and the responses are usually reactive rather than proactive in any event. This is a major problem for liberal democracies that value freedoms of speech and association because often the aim of recent adversarial sharp power campaigns (commonly labeled as disinformation campaigns) is to corrode domestic support for democracy as a form of governance. Because of their repressive nature, authoritarian regimes do not have quite the same problem when confronted by foreign direct influence operations. In that sense, as China and Russia have understood, freedoms of speech, movement and association in liberal democracies constitute Achilles heels that can be exploited by hybrid power direct influence campaigns.

Norm erosion, increased uncertainty and the rise of hybrid conflict as the systems regulator have encouraged the emergence of more authoritarian (here defined as command-oriented rather than consultative in approaches to governance and policy-making), less Western-centric approaches to international relations. The liberal international consensus failed to deliver on its promises in most of the post-colonial world as well as in many advanced democracies, so alternatives began to appear that challenged its basic premise. Many of these have a regressive character to them, characterised by a shift to economic nationalism, anti-immigration policies, and a focus on restoring “traditional” values. After decades of promoting free trade, multilateralism and open borders, the last decade has seen a turn inwards that has encouraged nationalistic authoritarian solutions to domestic and international problems.

National populism is one manifestation of the rejection of the liberal democratic order, and the Asian Values school of thought converged with anti-colonial and anti-imperialist sentiment to reject liberal internationalism on the global plane. Instead, the emphasis is on efficiency under strong centralised leadership grounded in nationalist principles rather than on transparency, multilateralism, inclusion and representativeness. Throughout the world democracy (both as a form of governance as well as a social characteristic) is in decline and authoritarianism is on the rise, with their attendant influence on the conduct of foreign policy and international relations.

This brings up one more aspect of transitional moments leading to systemic realignment: competition between rising and declining powers.

The shift between international systems is at its core the result of competition between ascendent and descend great powers. Ascendency and decline can be the result of economic, military, social or ideological factors. States in decline will attempt to maintain their positions against the challenges of new or resurgent rivals. The competition between them can theoretically be managed peacefully if States accept their fate and trust each other to engage with mutual respect. In reality, transitional competition between rising and declining powers is often existential in nature (at least in the eye of those involved), and if multidimensional conflict turns to war it is usually the declining power that starts it. World War I can be seen in this light, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine is a contemporary case in point. Although the US is also in decline, it is undergoing a gradual rather than a rapid loss of power and status. Instead of being a new form of politics, Trump and MAGA are the product of a deep long-term malaise that is as socio-cultural as it is political. Trumpism may act as an accelerant in hastening the US decline but it is not, as of yet, immediately terminal.

Russia, on the other hand, is faced with a societal decline (low birthrates, ageing population, pervasive corruption, export commodity dependence, severely distorted income distribution and social anomaly) that is immediate and likely irreversible. It has an economy equivalent in size to that of Spain or the US state of Texas rather than those of Japan, Germany, China or the US. The invasion of Ukraine, phrased in revisionist “return-to-Empire” language, is a last ditch effort to gain both people and land in order to arrest the decline (because annexing Eastern and Southern Ukraine would provide a younger population of Russian speakers, fertile agricultural lands, a non-extractive manufacturing base and warm water trading ports for Russian goods and imports).

Given Ukraine’s and the NATO response, this is akin to the last gasp of a drowning person. No matter whether it “wins” or loses, Russia will be permanently diminished by having undertaken this war. As it turns out, rather than the US, Russia is the great power whose decline motivated the march to war and which will precipitate the emergence of a new multipolar world order.

What might this new multipolar international system look like? A decade ago there was agreement that Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) would emerge as great powers and vie with the US on the global stage. India and China clearly remain as emerging great powers. However, Brazil and South Africa have failed to achieve that status due to internal dysfunctions exacerbated by poor political leadership. Rather than restore some of its Empire, Russia is committing an act of national Hara kiri in Ukraine and has lost its chance at genuine great power status in the post-war future .

So who might emerge if not the BRICs? Germany and Japan clearly have the resources and means to join the new multipolar constellation. Beyond that, the picture is cloudy. The UK is in obvious long-term decline and France is unable to elevate beyond its regional power status. No Middle Eastern, Latin American, SE Asia, Central Asian or African country can do more than become a regional power. Nordic and Mediterranean Europe States can complement but not replace powers like Germany in a multipolar world. Australia and Indonesia may someday emerge as rightful contenders for great power status but that day is a ways off. The US will remain as great rather than a superpower, so perhaps the making of a new multipolar order will involve it, China, India and restored Axis powers finally emerging from the ashes of WW2.

On interesting prospect is that both during the transition to a new multipolar world and once it has consolidated, small and medium States may have increased flexibility nd room to manoeuvre between the great powers. This is due to balancing focus of the new constellation, which its a premium on forging alliances on specific issues. That can encourage smaller states to get more involved in negotiations between the great powers, thereby augmenting their diplomatic influence in ways not seen before. On the other hand, if the opportunity is not recognised by the great powers or seized by smaller States, then the broadening of the multipolar constellation to include satellite alliances around specific great power positions will have been lost.

Hybridity as a transitional hallmark extends beyond warfare and traditional conflict and into the world of so-called “grey area phenomena.” It now refers to the the merging of criminal and State organisations in pursuit of a common purpose that serves their mutual interests. Cyber-hacking is the clearest case in point, where state actors like the Russian GRU signals intelligence unit collude with criminal organisations in cyber theft or cyber disruption campaigns. This hand-in-glove arrangement allows them to share technologies in pursuit of particular rewards: money for the criminals and intellectual property theft, security breaches or backdoor vulnerabilities in foreign networks for the state actor. China. Israel, North Korea and Iran are considered prime suspects of ending in such hybrid activities.

Externalities have been magnified during the long transitional moment. In particular, the Covid pandemic has revealed the crisis of contemporary capitalism and the relative levels of government incompetence around the world. The need to secure national borders and curtail the movement of people and goods across entire regions demonstrated that features like commodity concentration, “just-in-time” production, debt-leveraged financing and other late capitalist features exacerbated the costs of and impeded effective response to the pandemic. In turn, the pandemic exposed government corruption and incompetence on a global scale, where the Peter Principle (a person or agency rises to its own level of incompetence) separated efficient from failed pandemic mitigation policy. Where partisan politics interfered with the application of scientific health policy, the situation was made worse. The US, UK, Russia and Brazil are examples of the latter; NZ, Uruguay, Singapore and Taiwan are generally considered to be examples of the former.

What all of this means is that in the post-pandemic future multipolarity will emerge as the new global alignment under conditions of great uncertainty that produce different rules, prompt institutional reform and which promote different international behaviours. Capitalism will have to adapt and change (such as through near-shoring and friend-shoring investment strategies and a decentralisation of commodity production, perhaps including a return to national self-sufficiency in some productive areas and an embrace of competitive rather than comparative advantage economic strategies). “Living within our means” based on sustainability will become an increasingly common policy approach for those who understand the gravity of the moment.

The most change, however, is in the field of post-pandemic governance. The frailties of liberal democracy have been glaringly exposed, including corruption, lack of transparency, sclerotic systems of representation and voice, and pervasive nepotism and patronage in the linkage between constituents and elected officials. Authoritarians have emerged as alternatives in both historically democratic as well as traditionally undemocratic political systems, with that trend set to continue for the near future. That may or not be a salve rather than a solution to the deep seated problems afflicting global society but what it does demonstrate is that not only is the multipolar future uncertain to discern, but the systemic realignment may not necessarily lead to a more peaceful, egalitarian and representative constellation than what we have seen before.

Only time will tell what our future holds.

*This essay is written as a think piece that will serve as the basis for a public lecture the author will deliver to the World Affairs Forum in Auckland on October 10, 2022.

Media Link: “A View from Afar” on China, Taiwan and future implications.

The “A View from Afar” podcast with Selwyn Manning and I resumed after a months hiatus. We discussed the PRC-Taiwan tensions in the wake of Nancy Pelosi’s visit and what pathways, good and bad, may emerge from the escalation of hostilities between the mainland and island. You can find it here.

Considering Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan.

I have said this in other forums, but here is the deal:

PRC military exercises after Pelosi’s visit are akin to silverback male gorillas who run around thrashing branches and beating their chests when annoyed, disturbed or seeking to show dominance. They are certainly dangerous and not to be ignored, but their aggression is about signaling/posturing, not imminent attack. In other words, the behaviour is a demonstration of physical capabilities and general disposition rather than real immediate intent. If and when the PRC assault on Taiwan comes, it will not be telegraphed.

As for why Pelosi, third in the US chain of command, decided to go in spite of PRC threats and bluster. Along with a number of other factors, it was a show of bipartisan, legislative-executive branch resolve in support of Taiwan to allies and the PRC in a midterm election year. SecDef Austin was at her side, so Biden’s earlier claims that the military “did not think that her trip was a good idea” did not result in an institutional rupture over the issue. The show of unity was designed to allay allied concerns and adversary hopes that the US political elite is too divided to act decisively in a foreign crisis while removing a basis for conservative security hawk accusations in an election year that the Biden administration and Democrats are soft on China.

The PRC can threaten/exercise/engage indirect means of retaliation but cannot seriously escalate at this point. It’s launching of intermediate range ballistic missiles over Taiwan and into Japan’s EEZ as part of the response to Pelosi’s visit certainly deserves concerned attention by security elites, as it signals a readiness by the PRC to broaden the conflict into a regional war involving more than the US and Taiwan. But the PRC is too economically invested in Taiwan (especially in microchips and semi-conductors) to risk economic slow downs caused by disruptions of Taiwanese production in the event of war (which likely will be a protracted affair as Taiwan reverts to the “hedgehog” defence strategy common among island nations and facilitated by Formosa’s terrain), and it is not a full peer competitor with the US when it comes to the East Asian regional military balance, especially if US security allies join the conflict on Taiwan’s side.

The PRC must therefore bide its time and wait until its sea-air-land forces are capable of not only invading and occupying Taiwan, but be able to do so in the face of US-led military response across all kinetic and hybrid warfare domains. Pelosi’s visit was a not to subtle reminder of that fact.

So the visit, while provocative and an act of brinkmanship given the CCP is about to hold its 20th National Party Congress in which President Xi Jinping is expected to be re-elected unopposed to another term in office, was at its most basic level simply conveying a message that the US will not be bullied by the PRC on what was a symbolic visit to a disputed territory ruled by an independent democratic government.

For the moment the PRC must content itself with mock charges and thrashing the bush in the form of large-scale military exercises and some non-escalatory retaliation against the US and Taiwan, but it is unlikely to go beyond that at the moment. It remains to be seen if this sits well with nationalists and security hardliners in the CCP who may see what they perceive to be the relatively soft response as a loss of face and evidence of Xi’s lack of will to strike a blow for the Motherland when he has the chance and which could have also served as a good patriotic diversion from domestic woes caused by Covid and the ripple effect economic slowdown associated with it.

In that light, the Party Congress should give us a better idea if the factional undercurrents operating within the CCP will now spill out into the open over the Pelosi’s visit. If so, perhaps there was even more to the calculus behind her trip than what I have outlined above.

Countering coercive politics

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s two week foreign mission to Europe and Australia was by all accounts a success. She met with business and government leaders, signed and co-signed several commercial and diplomatic agreements including a EU-NZ trade pact, conferred with NATO officials as an invited participant of this year’s NATO’s Leader’s Summit, gave several keynote speeches on foreign policy and international affairs, and in general flew the Aotearoa flag with grace and a considerable dose of celebrity. As she wraps up her visit to Australia, it is worth noting that she gave different takes on foreign policy to different audiences. These may appear incongruous at first glance but in fact display a fair degree of strategic and diplomatic finesse.

In Europe she emphasized the commonality of shared values among liberal democracies across a range of subjects: approaches to trade, security, human rights, representative governance, the rule of law within and across borders, transparency and rejection of corruption, and the common threat posed to all of these values by authoritarian great powers that are trying to usurp the international order via persistent challenges and encroachments on international norms and institutions.

Towards the end of her trip while in Australia, she shifted tack and emphasized NZ’s “independent” foreign policy while dropping the value-based view of a global geostrategic contest marshalled along ideological lines.

Instead, she publicly decoupled the Ruso-Ukrainian war from broader geostrategic competition between democratic and authoritarian-led powers, treating Russian behavior as idiosyncratic rather than as a result of regime type. That framing of the conflict avoids messy arguments about domestic political legitimacy and its impact on great power rivalries. In doing so Ardern reaffirmed the independence of NZ’s foreign policy approach from those of larger Western allies while reducing the possibility of retaliation by the PRC on trade and other diplomatic fronts. The PRC is well aware of the reality of NZ’s recent strategic shift towards the West, but a public position that pointedly refuses to lump together PRC behavior with Russian aggression based on the authoritarian nature of their respective regimes gives NZ some time and diplomatic space in which to maneuver as it charts a course in the international transitional moment that it is currently navigating. That is a prudent position to take and hence a good diplomatic move assuming that the PRC reads the statement as NZ intends it to be read.

The strategy behind this approach–one that recognizes the larger ideological divide at play in international affairs but treats State actions as unique to individual national history and circumstances–might be called a “confronting coercive politics” approach. Allow me to explain.

Politics ultimately is about the acquisition, accumulation, administration, distribution, maintenance and loss of power. Power is the ability to make others bend to one’s will. It can be persuasive or coercive in nature, i.e., it can induce others to act in certain ways or it can compell them to act under (threat of) duress .

Power is relative and variable across several dimensions, including economic, political, military, personal, class, social (including gender and reputational/”influencer” in this day and age), cultural, intellectual and physical. Power is wielded directly or indirectly as a mixed bag of “hard” and “soft” attributes, a dichotomy that is well mentioned in the international relations and foreign policy literatures. Hybrid combinations of soft and hard power have led to “smart” and “sharp” power subsets depending on the emphasis given to one or the other basic trait.

The harder the exercise of power, the more coercive it is. Conversely, the more persuasive the way in which power is welded, the “softer” it is. Moreover, soft power can give way to hard power if the former is unsuccessful in accomplishing desired objectives, and soft power can be used as a follow up to the exercise of hard power. For example, “dollar diplomacy,” whereby large states fund development projects in small states on generous terms, is a form of soft power that can turn into hard power leverage once it becomes debt diplomacy in the form repayment conditions for those projects.

The exercise of State power has been institutionalized, codified and regulated over the years in a variety of contexts, including international relations and foreign policy. That is designed to strip inter-state relations of more overtly coercive approaches in favor of more consensus or compromise-oriented forms of engagement. However, in recent years the shift from a unipolar to a multipolar world-in-the-making has led to international norm erosion and a diminishing of international rule and law enforcement. That has produced a “back to the future” scenario where the international context has regressed to a modern version of the anarchic state of nature that Hobbes warned about in Leviathan. Emerging or restored great powers, particularly but not exclusively the PRC and Russia, have rejected international norms and laws in favor of a “might makes right” approach to international differences. Geopolitical coercion is at the heart of their international perspectives, which challenges the basic rules, norms and institutions of the liberal international order.

The turn towards more coercive forms of international politics is mirrored in the domestic politics of many States, including those led by democratic regimes. It is this–the emergence of coercive politics as a core feature of domestic and international governance–that is the focus of Ardern’s bifurcated foreign policy pronouncements in recent days. Her government understands that “liberal” governance is more than free and fair elections and respect for human rights. It is based on tolerance, compromise and mutual contingent consent between individuals, factions, parties and States.

Being unable to control the domestic regimes that govern States, Ardern’s bifurcated approach to NZ foreign policy (I would not call it a doctrine or anywhere close to one), is focused on countering coercive politics in international affairs. The general value principles of liberalism are upheld, but individual relations with other states, particularly important trade and security partners, are treated with a mix of value-based and pragmatic considerations, with pragmatism prevailing when strategic interests are at stake.

This approach allows NZ to broadly critique a trade partner’s human rights record while increasing or maintaining its trade with that partner in specific commodities under the argument that engagement with NZ’s values is better than isolation from them.

In other words, adherence in principle to liberal international values cloaks realistic assessments of where Aotearoa’s material interests are woven into the global institutional fabric. That may be cynical, hypocritical or short-sighted in its read of how the global order is evolving, but as a short-term diplomatic stance, it splits the difference between adherence to principle and amoral commitment to self-interested practice.

Media Link: “A View from Afar” on NATO and BRICS Leader’s summits.

Selwyn Manning and I discussed the upcoming NATO Leader’s summit (to which NZ Prime Minister Ardern is invited), the rival BRICS Leader’s summit and what they could mean for the Ruso-Ukrainian Wa and beyond.

Media Link: AVFA on Latin America.

In the latest episode of AVFA Selwyn Manning and I discuss the evolution of Latin American politics and macroeconomic policy since the 1970s as well as US-Latin American relations during that time period. We use recent elections and the 2022 Summit of the Americas as anchor points.

The PRC’s Two-Level Game.

Coming on the heels of the recently signed Solomon Islands-PRC bilateral economic and security agreement, the whirlwind tour of the Southwestern Pacific undertaken by PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi has generated much concern in Canberra, Washington DC and Wellington as well as in other Western capitals. Wang and the PRC delegation came to the Southwestern Pacific bearing gifts in the form of offers of developmental assistance and aid, capacity building (including cyber infrastructure), trade opportunities, economic resource management, scholarships and security assistance, something that, as in the case of the Solomons-PRC bilateral agreement, caught the “traditional” Western patrons by surprise. With multiple stops in Kiribati, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, PNG, Vanuatu and East Timor and video conferencing with other island states, Wang’s visit represents a bold outreach to the Pacific Island Forum community.

A couple of days ago I did a TV interview about the trip and its implications. Although I posted a link to the interview, I thought that I would flesh out was what unsaid in the interview both in terms of broader context as well as some of the specific issues canvassed during the junket. First, in order to understand the backdrop to recent developments, we must address some key concepts. Be forewarned: this is long.

China on the Rise and Transitional Conflict.

For the last three decades the PRC has been a nation on the ascent. Great in size, it is now a Great Power with global ambitions. It has the second largest economy in the world and the largest active duty military, including the largest navy in terms of ships afloat. It has a sophisticated space program and is a high tech world leader. It is the epicenter of consumer non-durable production and one of the largest consumers of raw materials and primary goods in the world. Its GDP growth during that time period has been phenomenal and even after the Covid-induced contraction, it has averaged well over 7 percent yearly growth in the decade since 2011.

The list of measures of its rise are many so will not be elaborated upon here. The hard fact is that the PRC is a Great Power and as such is behaving on the world stage in self-conscious recognition of that fact. In parallel, the US is a former superpower that has now descended to Great Power status. It is divided domestically and diminished when it comes to its influence abroad. Some analysts inside and outside both countries believe that the PRC will eventually supplant the US as the world’s superpower or hegemon. Whether that proves true or not, the period of transition between one international status quo (unipolar, bipolar or multipolar) is characterised by competition and often conflict between ascendent and descendent Great Powers as the contours of the new world order are thrashed out. In fact, conflict is the systems regulator during times of transition. Conflict may be diplomatic, economic or military, including war. As noted in previous posts, wars during moments of international transition are often started by descendent powers clinging or attempting a return to the former status quo. Most recently, Russia fits the pattern of a Great Power in decline starting a war to regain its former glory and, most importantly, stave off its eclipse. We shall see how that turns out.

Spheres of Influence.

More immediate to our concerns, the contest between ascendent and descendent Great Powers is seen in the evolution of their spheres of influence. Spheres of influence are territorially demarcated areas in which a State has dominant political, economic, diplomatic and military sway. That does not mean that the areas in question are as subservient as colonies (although they may include former colonies) or that this influence is not contested by local or external actors. It simply means at any given moment some States—most often Great Powers—have distinct and recognized geopolitical spheres of influence in which they have primacy of interest and operate as the dominant regional actor.

In many instances spheres of influence are the object of conquest by an ascendent power over a descendent power. Historic US dominance of the Western Hemisphere (and the Philippines) came at the direct expense of a Spanish Empire in decline. The rise of the British Empire came at the expense of the French and Portuguese Empires, and was seen in its appropriation of spheres of influence that used to be those of its diminished competitors. The British and Dutch spheres of influence in East Asia and Southeast Asia were supplanted by the Japanese by force, who in turn was forced in defeat to relinquish regional dominance to the US. Now the PRC has made its entrance into the West Pacific region as a direct peer competitor to the US.

Peripheral, Shatter and Contested Zones.

Not all spheres of influence have equal value, depending on the perspective of individual States. In geopolitical terms the world is divided into peripheral zones, shatter zones and zones of contestation. Peripheral zones are areas of the world where Great Power interests are either not in play or are not contested. Examples would be the South Pacific for most of its modern history, North Africa before the discovery of oil, the Andean region before mineral and nitrate extraction became feasible or Sub-Saharan Africa until recently. In the modern era spheres of influence involving peripheral zones tend to involve colonial legacies without signifiant economic value.

Shatter zones are those areas where Great Power interests meet head to head, and where spheres of influence clash. They involve territory that has high economic, cultural or military value. Central Europe is the classic shatter zone because it has always been an arena for Great Power conflict. The Middle East has emerged as a potential shatter zone, as has East Asia. The basic idea is that these areas are zones in which the threat of direct Great Power conflict (rather than via proxies or surrogates) is real and imminent, if not ongoing. Given the threat of escalation into nuclear war, conflict in shatter zones has the potential to become global in nature. That is a main reason why the Ruso-Ukrainian War has many military strategists worried, because the war is not just about Russia and Ukraine or NATO versus Russian spheres of influence.

In between peripheral and shatter zones lie zones of contestation. Contested zones are areas in which States vie for supremacy in terms of wielding influence, but short of direct conflict. They are often former peripheral zones that, because of the discovery of material riches or technological advancements that enhance their geopolitical value, become objects of dispute between previously disinterested parties. Contested zones can eventually become part of a Great Power’s sphere of influence but they can also become shatter zones when Great Power interests are multiple and mutually disputed to the point of war.

Strategic Balancing.

The interplay of States in and between their spheres of influence or as subjects of Great Power influence-mongering is at the core of what is known as strategic balancing. Strategic balancing is not just about relative military power and its distribution, but involves the full measure of a State’s capabilities, including hard, soft, smart and sharp powers, as it is brought to bear on its international relations.

That is the crux of what is playing out in the South Pacific today. The South Pacific is a former peripheral zone that has long been within Western spheres of influence, be they French, Dutch, British and German in the past and French, US and (as allies and junior partners) Australia and New Zealand today. Japan tried to wrest the West Pacific from Western grasp and ultimately failed. Now the PRC is making its move to do the same, replacing the Western-oriented sphere of influence status quo with a PRC-centric alternative.

The reason for the move is that the Western Pacific, and particularly the Southwestern Pacific has become a contested zone given technological advances and increased geopolitical competition for primary good resource extraction in previously unexploited territories. With small populations dispersed throughout an area ten times the size of the continental US covering major sea lines of communication, trade and exchange and with valuable fisheries and deep water mineral extraction possibilities increasingly accessible, the territory covered by the Pacific Island Forum countries has become a valuable prize for the PRC in its pursuit of regional supremacy. But in order to achieve this objective it must first displace the West as the major extra-regional patron of the Pacific Island community. That is a matter of strategic balancing as a prelude to achieving strategic supremacy.

Three Island Chains and Two Level Games.

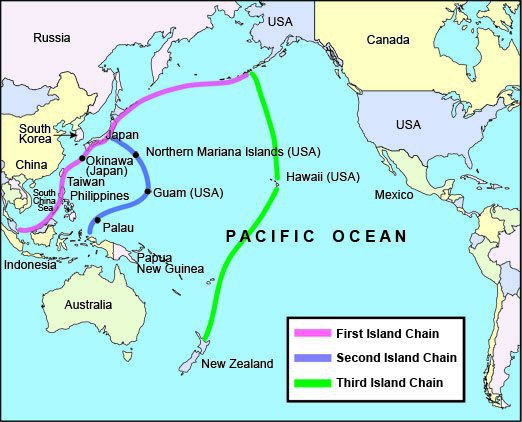

The core of the PRC strategy rests in a geopolitical conceptualization known as the “three island chains” This is a power projection perspective based on the PRC eventually gaining control of three imaginary chains of islands off of its East Coast. The first island chain, often referred to those included in the PRC’s “Nine Dash Line” mapping of the region, is bounded by Japan, Northwestern Philippines, Northern Borneo, Malaysia and Vietnam and includes all the waters within it. These are considered to be the PRC’s “inner sea” and its last line of maritime defense. This is a territory that the PRC is now claiming with its island-building projects in the South China Sea and increasingly assertive maritime presence in the East China Sea and the straits connecting them south of Taiwan.

The second island chain extends from Japan to west of Guam and north of New Guinea and Sulawesi in Indonesia, including all of the Philippines, Malaysian and Indonesian Borneo and the island of Palau. The third island chain, more aspirational than achievable at the moment, extends from the Aleutian Islands through Hawaii to New Zealand. It includes all of the Southwestern Pacific island states. It is this territory that is being geopolitically prepared by the PRC as a future sphere of influence, and which turns it into a contested zone.

(Source: Yoel Sano, Fitch Solutions)

The PRC approach to the Southwestern Pacific can be seen as a Two Level game. On one level the PRC is attempting to negotiate bilateral economic and security agreements with individual island States that include developmental aid and support, scholarship and cultural exchange programs, resource management and security assistance, including cyber security, police training and emergency security reinforcement in the event of unrest as well as “rest and re-supply” and ”show the flag” port visits by PLAN vessels. The Solomon Island has signed such a deal, and Foreign Minister Wang has made similar proposals to the Samoan and Tongan governments (the PRC already has this type of agreement in place with Fiji). The PRC has signed a number of specific agreements with Kiribati that lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive pact of this type in the future. With visits to Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and East Timor still to come, the approach has been replicated at every stop on Minister Wang’s itinerary. Each proposal is tailored to individual island State needs and idiosyncrasies, but the general blueprint is oriented towards tying development, trade and security into one comprehensive package.

None of this comes as a surprise. For over two decades the PRC has been using its soft power to cultivate friends and influence policy in Pacific Island states. Whether it is called checkbook or debt diplomacy (depending on whether developmental aid and assistance is gifted or purchased), the PRC has had considerable success in swaying island elite views on issues of foreign policy and international affairs. This has helped prepare the political and diplomatic terrain in Pacific Island capitals for the overtures that have been made most recently. That is the thrust of level one of this strategic game.

That opens the second level play. With a number of bilateral economic and security agreements serving as pillars or pilings, the PRC intends to propose a multinational regional agreement modeled on them. The first attempt at this failed a few days ago, when Pacific Island Forum leaders rejected it. They objected to a lack of detailed attention to specific concerns like climate change mitigation but did not exclude the possibility of a region-wide compact sometime in the future. That is exactly what the PRC wanted, because now that it has the feedback to its initial, purposefully vague offer, it can re-draft a regional pact tailored to the specific shared concerns that animate Pacific Island Forum discussions. Even if its rebuffed on second, third or fourth attempts, the PRC is clearly employing a “rinse, revise and repeat” approach to the second level aspect of the strategic game.

An analogy the captures the PRC approach is that of an off-shore oil rig. The bilateral agreements serve as the pilings or legs of the rig, and once a critical mass of these have been constructed, then an overarching regional platform can be erected on top of them, cementing the component parts into a comprehensive whole. In other words, a sphere of influence.

Western Reaction: Knee-Jerk or Nuanced?

The reaction amongst the traditional patrons has been expectedly negative. Washington and Canberra sent off high level emissaries to Honiara once the Solomon Islands-PRC deal was leaked before signature, in a futile attempt to derail it. The newly elected Australian Labor government has sent its foreign minister, sworn into office under urgency, twice to the Pacific in two weeks (Fiji, Tonga and Samoa) in the wake of Minister Wang’s visits. The US is considering a State visit for Fijian Prime Minister (and former dictator) Frank Baimimarama. The New Zealand government has warned that a PRC military presence in the region could be seriously destabilising and signed on to a joint US-NZ statement at the end of Prime Minister Ardern’s trade and diplomatic junket to the US re-emphasising (and deepening) the two countries’ security ties in the Pacific pursuant to the Wellington and Washington Agreements of a decade ago.