In the latest episode of AVFA Selwyn Manning and I discuss the evolution of Latin American politics and macroeconomic policy since the 1970s as well as US-Latin American relations during that time period. We use recent elections and the 2022 Summit of the Americas as anchor points.

The PRC’s Two-Level Game.

Coming on the heels of the recently signed Solomon Islands-PRC bilateral economic and security agreement, the whirlwind tour of the Southwestern Pacific undertaken by PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi has generated much concern in Canberra, Washington DC and Wellington as well as in other Western capitals. Wang and the PRC delegation came to the Southwestern Pacific bearing gifts in the form of offers of developmental assistance and aid, capacity building (including cyber infrastructure), trade opportunities, economic resource management, scholarships and security assistance, something that, as in the case of the Solomons-PRC bilateral agreement, caught the “traditional” Western patrons by surprise. With multiple stops in Kiribati, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, PNG, Vanuatu and East Timor and video conferencing with other island states, Wang’s visit represents a bold outreach to the Pacific Island Forum community.

A couple of days ago I did a TV interview about the trip and its implications. Although I posted a link to the interview, I thought that I would flesh out was what unsaid in the interview both in terms of broader context as well as some of the specific issues canvassed during the junket. First, in order to understand the backdrop to recent developments, we must address some key concepts. Be forewarned: this is long.

China on the Rise and Transitional Conflict.

For the last three decades the PRC has been a nation on the ascent. Great in size, it is now a Great Power with global ambitions. It has the second largest economy in the world and the largest active duty military, including the largest navy in terms of ships afloat. It has a sophisticated space program and is a high tech world leader. It is the epicenter of consumer non-durable production and one of the largest consumers of raw materials and primary goods in the world. Its GDP growth during that time period has been phenomenal and even after the Covid-induced contraction, it has averaged well over 7 percent yearly growth in the decade since 2011.

The list of measures of its rise are many so will not be elaborated upon here. The hard fact is that the PRC is a Great Power and as such is behaving on the world stage in self-conscious recognition of that fact. In parallel, the US is a former superpower that has now descended to Great Power status. It is divided domestically and diminished when it comes to its influence abroad. Some analysts inside and outside both countries believe that the PRC will eventually supplant the US as the world’s superpower or hegemon. Whether that proves true or not, the period of transition between one international status quo (unipolar, bipolar or multipolar) is characterised by competition and often conflict between ascendent and descendent Great Powers as the contours of the new world order are thrashed out. In fact, conflict is the systems regulator during times of transition. Conflict may be diplomatic, economic or military, including war. As noted in previous posts, wars during moments of international transition are often started by descendent powers clinging or attempting a return to the former status quo. Most recently, Russia fits the pattern of a Great Power in decline starting a war to regain its former glory and, most importantly, stave off its eclipse. We shall see how that turns out.

Spheres of Influence.

More immediate to our concerns, the contest between ascendent and descendent Great Powers is seen in the evolution of their spheres of influence. Spheres of influence are territorially demarcated areas in which a State has dominant political, economic, diplomatic and military sway. That does not mean that the areas in question are as subservient as colonies (although they may include former colonies) or that this influence is not contested by local or external actors. It simply means at any given moment some States—most often Great Powers—have distinct and recognized geopolitical spheres of influence in which they have primacy of interest and operate as the dominant regional actor.

In many instances spheres of influence are the object of conquest by an ascendent power over a descendent power. Historic US dominance of the Western Hemisphere (and the Philippines) came at the direct expense of a Spanish Empire in decline. The rise of the British Empire came at the expense of the French and Portuguese Empires, and was seen in its appropriation of spheres of influence that used to be those of its diminished competitors. The British and Dutch spheres of influence in East Asia and Southeast Asia were supplanted by the Japanese by force, who in turn was forced in defeat to relinquish regional dominance to the US. Now the PRC has made its entrance into the West Pacific region as a direct peer competitor to the US.

Peripheral, Shatter and Contested Zones.

Not all spheres of influence have equal value, depending on the perspective of individual States. In geopolitical terms the world is divided into peripheral zones, shatter zones and zones of contestation. Peripheral zones are areas of the world where Great Power interests are either not in play or are not contested. Examples would be the South Pacific for most of its modern history, North Africa before the discovery of oil, the Andean region before mineral and nitrate extraction became feasible or Sub-Saharan Africa until recently. In the modern era spheres of influence involving peripheral zones tend to involve colonial legacies without signifiant economic value.

Shatter zones are those areas where Great Power interests meet head to head, and where spheres of influence clash. They involve territory that has high economic, cultural or military value. Central Europe is the classic shatter zone because it has always been an arena for Great Power conflict. The Middle East has emerged as a potential shatter zone, as has East Asia. The basic idea is that these areas are zones in which the threat of direct Great Power conflict (rather than via proxies or surrogates) is real and imminent, if not ongoing. Given the threat of escalation into nuclear war, conflict in shatter zones has the potential to become global in nature. That is a main reason why the Ruso-Ukrainian War has many military strategists worried, because the war is not just about Russia and Ukraine or NATO versus Russian spheres of influence.

In between peripheral and shatter zones lie zones of contestation. Contested zones are areas in which States vie for supremacy in terms of wielding influence, but short of direct conflict. They are often former peripheral zones that, because of the discovery of material riches or technological advancements that enhance their geopolitical value, become objects of dispute between previously disinterested parties. Contested zones can eventually become part of a Great Power’s sphere of influence but they can also become shatter zones when Great Power interests are multiple and mutually disputed to the point of war.

Strategic Balancing.

The interplay of States in and between their spheres of influence or as subjects of Great Power influence-mongering is at the core of what is known as strategic balancing. Strategic balancing is not just about relative military power and its distribution, but involves the full measure of a State’s capabilities, including hard, soft, smart and sharp powers, as it is brought to bear on its international relations.

That is the crux of what is playing out in the South Pacific today. The South Pacific is a former peripheral zone that has long been within Western spheres of influence, be they French, Dutch, British and German in the past and French, US and (as allies and junior partners) Australia and New Zealand today. Japan tried to wrest the West Pacific from Western grasp and ultimately failed. Now the PRC is making its move to do the same, replacing the Western-oriented sphere of influence status quo with a PRC-centric alternative.

The reason for the move is that the Western Pacific, and particularly the Southwestern Pacific has become a contested zone given technological advances and increased geopolitical competition for primary good resource extraction in previously unexploited territories. With small populations dispersed throughout an area ten times the size of the continental US covering major sea lines of communication, trade and exchange and with valuable fisheries and deep water mineral extraction possibilities increasingly accessible, the territory covered by the Pacific Island Forum countries has become a valuable prize for the PRC in its pursuit of regional supremacy. But in order to achieve this objective it must first displace the West as the major extra-regional patron of the Pacific Island community. That is a matter of strategic balancing as a prelude to achieving strategic supremacy.

Three Island Chains and Two Level Games.

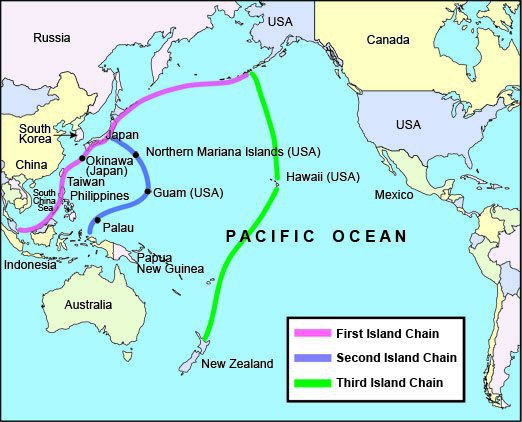

The core of the PRC strategy rests in a geopolitical conceptualization known as the “three island chains” This is a power projection perspective based on the PRC eventually gaining control of three imaginary chains of islands off of its East Coast. The first island chain, often referred to those included in the PRC’s “Nine Dash Line” mapping of the region, is bounded by Japan, Northwestern Philippines, Northern Borneo, Malaysia and Vietnam and includes all the waters within it. These are considered to be the PRC’s “inner sea” and its last line of maritime defense. This is a territory that the PRC is now claiming with its island-building projects in the South China Sea and increasingly assertive maritime presence in the East China Sea and the straits connecting them south of Taiwan.

The second island chain extends from Japan to west of Guam and north of New Guinea and Sulawesi in Indonesia, including all of the Philippines, Malaysian and Indonesian Borneo and the island of Palau. The third island chain, more aspirational than achievable at the moment, extends from the Aleutian Islands through Hawaii to New Zealand. It includes all of the Southwestern Pacific island states. It is this territory that is being geopolitically prepared by the PRC as a future sphere of influence, and which turns it into a contested zone.

(Source: Yoel Sano, Fitch Solutions)

The PRC approach to the Southwestern Pacific can be seen as a Two Level game. On one level the PRC is attempting to negotiate bilateral economic and security agreements with individual island States that include developmental aid and support, scholarship and cultural exchange programs, resource management and security assistance, including cyber security, police training and emergency security reinforcement in the event of unrest as well as “rest and re-supply” and ”show the flag” port visits by PLAN vessels. The Solomon Island has signed such a deal, and Foreign Minister Wang has made similar proposals to the Samoan and Tongan governments (the PRC already has this type of agreement in place with Fiji). The PRC has signed a number of specific agreements with Kiribati that lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive pact of this type in the future. With visits to Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and East Timor still to come, the approach has been replicated at every stop on Minister Wang’s itinerary. Each proposal is tailored to individual island State needs and idiosyncrasies, but the general blueprint is oriented towards tying development, trade and security into one comprehensive package.

None of this comes as a surprise. For over two decades the PRC has been using its soft power to cultivate friends and influence policy in Pacific Island states. Whether it is called checkbook or debt diplomacy (depending on whether developmental aid and assistance is gifted or purchased), the PRC has had considerable success in swaying island elite views on issues of foreign policy and international affairs. This has helped prepare the political and diplomatic terrain in Pacific Island capitals for the overtures that have been made most recently. That is the thrust of level one of this strategic game.

That opens the second level play. With a number of bilateral economic and security agreements serving as pillars or pilings, the PRC intends to propose a multinational regional agreement modeled on them. The first attempt at this failed a few days ago, when Pacific Island Forum leaders rejected it. They objected to a lack of detailed attention to specific concerns like climate change mitigation but did not exclude the possibility of a region-wide compact sometime in the future. That is exactly what the PRC wanted, because now that it has the feedback to its initial, purposefully vague offer, it can re-draft a regional pact tailored to the specific shared concerns that animate Pacific Island Forum discussions. Even if its rebuffed on second, third or fourth attempts, the PRC is clearly employing a “rinse, revise and repeat” approach to the second level aspect of the strategic game.

An analogy the captures the PRC approach is that of an off-shore oil rig. The bilateral agreements serve as the pilings or legs of the rig, and once a critical mass of these have been constructed, then an overarching regional platform can be erected on top of them, cementing the component parts into a comprehensive whole. In other words, a sphere of influence.

Western Reaction: Knee-Jerk or Nuanced?

The reaction amongst the traditional patrons has been expectedly negative. Washington and Canberra sent off high level emissaries to Honiara once the Solomon Islands-PRC deal was leaked before signature, in a futile attempt to derail it. The newly elected Australian Labor government has sent its foreign minister, sworn into office under urgency, twice to the Pacific in two weeks (Fiji, Tonga and Samoa) in the wake of Minister Wang’s visits. The US is considering a State visit for Fijian Prime Minister (and former dictator) Frank Baimimarama. The New Zealand government has warned that a PRC military presence in the region could be seriously destabilising and signed on to a joint US-NZ statement at the end of Prime Minister Ardern’s trade and diplomatic junket to the US re-emphasising (and deepening) the two countries’ security ties in the Pacific pursuant to the Wellington and Washington Agreements of a decade ago.

The problem with these approaches is two-fold, one general and one specific. If countries like New Zealand and its partners proclaim their respect for national sovereignty and independence, then why are they so perturbed when a country like the Solomon Islands signs agreements with non-traditional patrons like the PRC? Besides the US history of intervening in other countries militarily and otherwise, and some darker history along those lines involving Australian and New Zealand actions in the South Pacific, when does championing of sovereignty and independence in foreign affairs become more than lip service? Since the PRC has no history of imperialist adventurism in the South Pacific and worked hard to cultivate friends in the region with exceptional displays of material largesse, is it not a bit neo-colonial paternalistic of Australia, NZ and the US to warn Pacific Island states against engagement with it? Can Pacific Island states not find out themselves what is in store for them should they decide to play the Two Level Game?

More specifically, NZ, Australia and the US have different security perspectives regarding the South Pacific. The US has a traditional security focus that emphasises great power competition over spheres of influence, including the Western Pacific Rim. It has openly said that the PRC is a threat to the liberal, rules-based international order (again, the irony abounds) and a growing military threat to the region (or at least US military supremacy in it). As a US mini-me or Deputy Sheriff in the Southern Hemisphere, Australia shares the US’s traditional security perspective and emphasis when it comes to threat assessments, so its strategic outlook dove-tails nicely with its larger 5 Eyes partner.

New Zealand, however, has a non-traditional security perspective on the Pacific that emphasises the threats posed by climate change, environmental degradation, resource depletion, poor governance, criminal enterprise, poverty and involuntary migration. As a small island state, NZ sees itself in a solidarity position with and as a champion of its Pacific Island neighbours when it comes to representing their views in international fora. Yet it is now being pulled by its Anglophone partners into a more traditional security perspective when it comes to the PRC in the Pacific, something that in turn will likely impact on its relations with the Pacific Island community, to say nothing of its delicate relationship with the PRC.

In any event, the Southwestern Pacific is a microcosmic reflection of an international system in transition. The issue is whether the inevitable conflicts that arise as rising and falling Great Powers jockey for position and regional spheres of influence will be resolved via coercive or peaceful means, and how one or the other means of resolution will impact on their allies, partners and strategic objects of attention such as the Pacific Island community.

In the words of the late Donald Rumsfeld, those are the unknown unknowns.

Approaching storm over the horizon.

The Solomon Islands and PRC have signed a bilateral security pact. The news of the pact was leaked a month ago and in the last week the governments of both countries have confirmed the deal. However, few details have been released. What we do know is that Chinese police trainers are already working with the Solomons Island police on tactics like crowd control, firearms use, close protection and other operating procedures that have been provided by the Australian and New Zealand police since the end of the RAMSI peace-keeping mission in 2017. More Chinese cops are to come, likely to replace the last remnants of the OZ and NZ police contingents. What is novel is that the agreement allows the PRC to deploy security forces in order to protect Chinese investments and diaspora communities in the event of public unrest. That is understandable because the PRC is the biggest investor in the Solomon Islands (mostly in forestry) and Chinese expats and their properties and businesses have regularly been on the receiving end of mob violence when social and political tensions explode.

Allowing Chinese security forces to protect Chinese economic interests and ex-pats on foreign soil has brought a new twist to the usual security diplomacy boilerplate, one that could be emulated in other Pacific Island states with large Chinese populations. Given the large amounts of PRC economic assistance to Pacific Island states before and during the Belt and Road initiative, which has often been referred to as “dollar,” then “debt” diplomacy because it involves Chinese financing and/or the gifting of large developmental projects to island states in which imported Chinese labor is used and where it is suspected that PRC money was passed to local officials in order to grease the way for contracts to be let, the possibility of this new type of security agreement is now firmly on the diplomatic table.

Also very worth noting is that the SI-PRC agreement gives the Chinese Navy (PLAN) berthing and logistical support rights during port visits, with the Chinese ugrading the port of Honiara in order to accommodate the deep draft grey hulls that it will be sending that way. This has raised fears in Western security circles that the current deal is a precursor to a forward basing agreement like the one the PRC has with Djibouti, with PLA troops and PLAN vessels permanently stationed on a rotating basis on Solomon Islands soil. Given that the Solomon Islands sit astride important sea lanes connecting Australia (and New Zealand) with the Northwestern Pacific Rim as well as waters further East, this is seen as a move that will upset the strategic balance in the Southwest Pacific to the detriment of the Western-dominant status quo that currently exists.

The fear extends to concerns about the PRC inking similar agreements with Fiji (with whom its already has a port visit agreement), Samoa and Tonga. The PRC has invested heavily in all three countries and maintains signals collection facilities at its embassies in Suva and Nuku’alofa. A forward basing agreement with any of them would allow the PLAN to straddle the sea lanes between the Coral Sea and larger Pacific, effectively creating a maritime chokepoint for commercial and naval shipping.

Needless to say, the reaction in Australia, NZ and the US has been predictably negative and sometimes borderline hysterical. For example, recent reports out of Australia claim that Chinese troops could be on the ground in the Solomons within a month. If true and if some Australian/NZ commentators are correct in their assessments, the only implicit options left to reverse the PRC-Solomons security agreement in the diminishing time window before the PRC establishes a firm foothold in Honiara is either by fomenting a coup or by direct military intervention. Opposition (and pro-Taiwan) Malaitan militias might be recruited for either venture (the Solomons switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the PRC in 2019, something that was widely opposed on the island of Malaita). However, PM Sogavare already has PRC police in country and can invoke the new deal to get rapid response PRC units on the ground to quash an uprising or resist foreign military intervention. So the scene is set for a return to the nation-wide violence of two decades ago, but in which contending foreign intervention forces are joined to inter-tribal violence.

The agreement is also a test of NZ and OZ commitments to the principles of national sovereignty and self-determination. Left-leaning pundits see the deal as benign and Western concerns as patronizing, racist and evidence of a post-colonial mentality. Right-leaning mouthpieces see it as the first PRC toe- hold on its way to regional strategic domination (hence the need for pre-emptive action). Both the New Zealand and Australian governments have expressed concerns about the pact but stopped short of threatening coercive diplomacy to get Sogavare to reverse course and rescind the deal. Australia has sent its Minister for Pacific affairs to Honiara to express its concern and the US has sent a fairly high (Assistant Secretary) level delegation to reaffirm its commitment to regional peace and stability. NZ has refrained from sending a crisis diplomatic delegation to Honiara, perhaps because the Prime Minister is on an Asian junket in which the positives of newly signed made and cultural exchanges are being touted and negative developments are being downplayed. But having been involved with such contingency-planning matters in my past, intelligence and military agencies are well into gaming any number of short to medium term scenarios including those involving force, and their contingency planning scenarios may not be driven by respect for norms and principles involving Solomon Islands sovereignty, self-determination and foreign policy independence.

Conspicuous by their absence have been the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) and the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG). The former is the regional diplomatic grouping founded in 1971 and Headquartered in Suva, Fiji. It is comparable to the Organization of American States (OAS), Organization of African Unity (OAU) or Southeast Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO). It has several security clauses in its charter, including that 2000 Biketawa Declaration that sets the framework for regional crisis management and conflict resolution and which was invoked to authorise the Regional Assistance Mission for the Solomon Islands (RAMSI) from 2003-2017.

The latter was formally incorporated in 1988 (Fiji was admitted in 1996) as a Melanesian anti-colonial solidarity organization and trade and cultural facilitator involving PNG, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and the Kanak National Liberation Front (FLINKS) in New Caledonia. It subsequently admitted observer missions from Indonesia (now Associate Member), Timor Leste and the United Liberation Movement of West Papua.

Currently headquartered in Port Villa, Vanuatu, under Fiji’s leadership in the late 2000s it attempted to re-position itself as a regional security intervention body for Melanesia, (prompted by the unrest in the Solomons and Papua New Guinea in the early 2000s). That initiative never prospered and the MSG remains as more of a symbolic grouping than one with serious diplomatic weight in spite of the signing of an MSG regional trade agreement in 1996 (revised in 2005) and Fijian Prime Minister Bainimarama’s attempts to make it a vehicle for loftier ambitions.

Neither agency has weighed in at any significant length on the agreement or the response from the traditional Western patrons. That may have something to do with the PRC’s dollar diplomacy shifting regional perspectives on diplomacy and security, or perhaps has to do with long-standing unhappiness with the approaches of “traditional” Western patrons when it comes to broader issues of development and trade (since the PC-SI security deal also includes clauses about “humanitarian” and developmental assistance). The MSG silence is significant because it has the potential to serve as a regional peace-keeping force deployed mainly to deal with ethnic and tribal unrest in member states as well as inter-state conflict, thereby precluding the need for non-Melanesian powers to get involved in domestic or regional security matters. Either way, the absence of the Solomon Island’s closets neighbours in a glaring omission from diplomatic discussions about how to respond to the agreement.

That is a good reason for the PIF and MSG to be engaged in resolving the inevitable disputes that will arise amid the fallout from the PRC-SI security agreement. It could involve setting boundaries for foreign military operations (such as limiting foreign military presences to anti-poaching, anti-smuggling or anti-piracy missions) or limits to foreign military basing and fleet numbers. It could involve negotiating MSG control over domestic public order measures and operations in the event of internal unrest, including those involving the PRC and Western traditional patrons. The main point is that regional organizations take the lead in administering regional security affairs covering the nature and limits of bilateral relations between member states and extra-regional powers (including traditional patrons as well as newer aspirants).

Whatever happens, it might be best to wait until the agreement details are released (and it remains to be seen if they will be) and save the sabre rattling for then should the worst (Western) fears are realized. That sabre rattling scenario includes a refusal to release the full details of the pact or dishonesty in presenting its clauses (especially given PRC track record of misrepresentations regarding its ambitions in the South China Sea and the nature of the island-building projects on reefs claimed by other littoral states bordering it). Of course, if the agreement details are withheld or misrepresented or the PRC makes a pre-emptive move of forces anticipating the OZ/NZ coercive response, then all bets are off as to how things will resolve. The window of diplomatic opportunity to strike an equitable resolution to the issue is therefore short and the possibility of negative consequences in the event that it is not loom large over the Pacific community and beyond.

In other words, it is time for some hard-nosed geopolitical realist cards to be placed on the diplomatic table involving interlocutors big and small, regional and extra-regional, without post-colonial patronizing, anti-imperialist “whataboutism” or yellow fever-style fear-mongering. Because a new strategic balance is clearly in the making, and the only question remaining is whether it will be drafted by lead or on paper.

Media Link: AVFA on small state approaches to multilateral conflict resolution in transitional times.

In this week’s “A View from Afar” podcast Selwyn Manning and I used NZ’s contribution of money to purchase weapons for Ukraine as a stepping stone into a discussion of small sate roles in coalition-building, multilateral approaches to conflict resolution and who and who is not aiding the effort to stem the Russian invasion. We then switch to a discussion of the recently announced PRC-Solomon Islands security agreement and the opposition to it from Australia, NZ and the US. As we note, when it comes to respect for sovereignty and national independence in foreign policy, in the cases of Ukraine and the Solomons, what is good for the goose is good for the gander.

We got side-tracked a bit with a disagreement between us about the logic of nuclear deterrence as it might or might not apply to the Ruso-Ukrainian conflict, something that was mirrored in the real time on-line discussion. That was good because it expanded the scope of the storyline for the day, but it also made for a longer episode. Feel free to give your opinions about it.

Media Link: AVFA on the Open Source Intelligence War.

I have been busy with other projects so have not been posting as much as I would like. Hence the turn to linking to episodes from this season ‘s “A View from Afar” podcast with Selwyn Manning (this is season 3, episode 8). In the month since the Russians invaded Ukraine we have dedicated our shows to various aspects of the war. We continue that theme this week by using as a “hook” the news that New Zealand is sending 7 signals intelligence specialists to London and Brussels to assist NATO with its efforts to supply Ukraine with actionable real time signals and technical intelligence in its fight against the invaders. We take that a step further by discussing the advent of open source intelligence collection and analysis as not only the work of private commercial ventures and interested individuals and scholars, but as a crowd sourcing effort that is in tis case being encouraged and channeled by the Ukrainian government and military to help tip the conflict scales in its favour.

We also discuss the geopolitical reasons why NZ decided to make the move when it arguably has no dog directly involved in the fight. It turns out that it does.

Media Link: the Ruso-Ukrainian war as a systemic realignment.

In this week’s A View From Afar podcast Selwyn Maninng and I explore the longer transitional moment that has brought the international system to where it is today, and where it might be headed in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Russia-Ukraine, round 3: the military and sanctions fronts.

Continuing our focus on the Russian-Ukrainian crisis, Selwyn Manning and I used this week’s “A View from Afar” podcast to examine the state of play on the battlefield and with regard to the sanctions regime being built against Russia. There is cause for both alarm and optimism.

Media link: the Russia-Ukraine crisis unfolds, redux.

In this week’s “A View from Afar” podcast Selwyn Manning and I continue our discussion about the Russian-Ukraine crisis even as Russian troops began their invasion into the latter country. Of necessity it had to be speculative about events on the ground, but it also widens out the the discussion to consider the short-term implications of the conflict. You can find the podcast here.

Media Link: “A View from Afar” podcast season 3, episode 3 on the geopolitics of the Ukrainian crisis.

In this podcast Selwyn Manning and I look into the tensions surrounding the threatened Russian invasion of the Ukraine and the geopolitical backdrop, diplomatic standoff and practicalities involved should an invasion occur. In summary, Russia wants to “Findlandize” more than the just the Ukraine and, if it cannot do so by threatening war, then it can certainly do so by waging a limited war of territorial conquest in parts of the country where ethnic Russians dominate the local demographic (the Donbass region, especially around Donetsk and Luhansk). It does not have to try and seize, hold, then occupy the entire country in order to get its point across to NATO about geopolitical buffer zones on its Western borders. In fact, to do so would be counter-productive and costly for the Kremlin even if no military power overtly intervenes on Ukraine’s behalf.

You can find the podcast here.

Redrawing the lines.

Early this year I was asked by a media outlet to appear and offer predictions on what will happen in world affairs in 2022. That was a nice gesture but I wound up not doing the show. However, as readers may remember from previous commentary about the time and effort put into (most often unpaid) media preparation, I engaged in some focused reading on international relations and comparative foreign policy before I decided to pull the plug on the interview. Rather than let that research go to waste I figured that I would briefly outline my thoughts about that may happen this year. They are not so much predictions as they are informal futures forecasting over the near term horizon.

The year is going to see an intensification of the competition over the nature of the framework governing International relations. If not dead, the liberal institutional order that dominated global affairs for the better part of the post-Cold War period is under severe stress. New and resurgent great powers like the PRC and Russia are asserting their anti-liberal preferences and authoritarian middle powers such as Turkey, North Korea, Saudi Arabia and Iran are defying long-held conventions and norms in order to assert their interests on the regional and world stages. The liberal democratic world, in whose image the liberal international order was ostensibly made, is in decline and disarray. In this the US leads by example, polarized and fractured at home and a weakened, retreating, shrinking presence on the world stage. It is not alone, as European democracies all have versions of this malaise, but it is a shining example of what happens when a superpower over-extends itself abroad while treating domestic politics as a centrifugal zero sum game.

While democracies have weakened from within, modern authoritarians have adapted to the advanced telecommunications and social media age and modified their style of rule (such as holding legitimating elections that are neither fair or free and re-writing constitutions that perpetuate their political control) while keeping the repressive essence of it. They challenge or manipulate the rule of law and muscle their way into consolidating power and influence at home and abroad. In a number of countries democratically elected leaders have turned increasingly authoritarian. Viktor Orban In Hungary, Recep Erdogan in Turkey, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, and Narendra Modi in India (whose Hindutva vision of India as an ethno-State poses serious risks for ethnic and religious minorities), all evidence the pathology of authoritarianism “from within.”

Abroad, authoritarians are on the move. China continues its aggressive maritime expansion in the East and South China Seas and into the Pacific while pushing its land borders outwards, including annexing territory in the Kingdom of Bhutan and clashing with Indian troops for territorial control on the Indian side of their Himalayan border. Along with military interventions in Syria, Libya and recently Kazakstan, Russia has annexed parts of Georgia and the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine, taken control of Crimea, and is now massing troops on the Ukrainian border while it demands concessions from NATO with regard to what the Russians consider to be unacceptable military activity in the post-Soviet buffer zone on its Western flank. The short term objective of the latest move is to promote fractures within NATO over its collective response, including the separation of US security interests from those of its continental partners. The long term intention is to “Findlandize” countries like Ukraine, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania so that they remain neutral, or at least neutralized, in the event of major conflict between Russia and Western Europe. As Churchill is quoted as saying, but now applied to Vladimir Putin, “he may not want war. He just wants the fruits of war.”

>>Aside about Russia’s threat to the Ukraine: The Russians are now in full threat mode but not in immediate invasion mode. To do that they need to position water and fuel tankers up front among the armoured columns that will be needed to overcome Ukrainian defences, and the 150,000 Russian troops massed on the eastern Ukrainian border are not sufficient to occupy the entire country for any length of time given Ukrainian resistance capabilities, including fighting a protracted guerrilla war on home soil (at least outside Russian ethnic dominant areas in eastern Ukraine). The Russians know that they are being watched, and satellite imagery shows no forward positioning of the logistical assets needs to seize and hold Ukrainian territory for any length of time. Paratroops and light infantry cannot do that, and while the Russians can rapidly deploy support for the heavier forces that can seize and hold hostile territory, this Russian threat appears to be directed, at best, at a limited incursion into Russian-friendly (read ethnic) parts of eastern Ukraine. That gives the Ukrainians and their international supporters room for negotiation and military response, both of which may be essential to deter Russian ambitions vis a vis the fundamental structure and logic of European security.<<

Rather than detail all the ways in which authoritarians are ascendent and democrats descendent in world affairs, let us look at the systemic dynamics at play. What is occurring is a shift in the global balance of power. That balance is more than the rise and decline of great powers and the constellations aggregated around them. It is more than about uni-, bi-, and multipolarity. It refers to the institutional frameworks, norms, practices and laws that govern the contest of States and other international actors. That arrangement—the liberal international order–is what is now under siege. The redrawing of lines now underway is not one of maps but of mores.

The liberal international order was essentially a post-colonial creation made by and for Western imperialist states after the war- and Depression-marked interregnum of the early 20th century. It did not take full hold until the collapse of the Soviet Union, as Cold War logics led to a tight bipolar international system in which the supposed advantages of free trade and liberal democracy were subordinated to the military deterrence imperatives of the times. This led to misadventures and aberrations like the domino theory and support for rightwing dictators on the part of Western Powers and the crushing of domestic political uprisings by the Soviets in Eastern Europe, none of which were remotely “liberal” in origin or intent.

After the Cold War liberal internationalists rose to positions of prominence in many national capitals and international organizations. Bound together by elite schooling and shared perspectives gained thereof, these foreign policy-makers saw in the combination of democracy and markets the best possible political-economic combine. They consequently framed much of their decision-making around promoting the twin pillars of liberal internationalism in the form of political democratization at the national level and trade opening on a global scale via the erection of a latticework of bi- and multilateral “free” trade agreements (complete with reductions in tariffs and taxes on goods and services but mostly focused on investor guarantee clauses) around the world.

The belief in liberal internationalism was such that it was widely assumed that inviting the PRC, Russia and other authoritarian regimes into the community of nations via trade linkages would lead to their eventual democratization once domestic polities began to experience the material advantages of free market capitalism on their soil. This was the same erroneous assumption made by Western modernization theorists in the 1950s, who saw the rising middle classes as “carriers” of democratic values even in countries with no historical or cultural experience with that political regime type or the egalitarian principles underbidding it. Apparently unwilling to read the literature on why modernization theory did not work in practice, in the 1990s neo-modernization theorists re-invented the wheel under the guise of the Washington Consensus and other such pro-market institutional arrangements regulating international commerce.

Like the military-bureaucratic authoritarians of the 1960s and 1970s who embraced and benefited from the application of modernization theory to their local circumstances (including sub-sets such as the Chicago School of macroeconomics that posited that finance capital should be the leader of national investment decisions in an economic environment being restructured via the privatization of public assets), in the 1990s the PRC and Russia welcomed Western investment and expansion of trade without engaging in the parallel path of liberalizing, then democratizing their internal politics. In fact, the opposite has occurred: as both countries became more capitalistic they became increasingly authoritarian even if they differ in their specifics (Russia is a oligopolistic kleptocracy whereas the PRC is a one party authoritarian, state capitalist system). Similarly, Turkey has enjoyed the fruits of capitalism while dismantling the post-Kemalist legacy of democratic secularism, and the Sunni Arab petroleum oligarchies have modernized out of pre-capitalist fossil fuel extraction enclaves into diversified service hubs without significantly liberalizing their forms of rule. A number of countries such as Brazil, South Africa and the Philippines have backslid at a political level when compared to the 1990s while deepening their ties to international capital. Likewise, after a period of optimism bracketed by events like the the move to majority rule in South Africa and the “Arab Spring,” both Saharan and Sub-Saharan Africa have in large measure reverted to the rule of strongmen and despots.

As it turns out, as the critics of modernisation theory noted long ago, capitalism has no elective affinity for democracy as a political form (based on historical experience one might argue to the contrary) and democracy is no guarantee that capitalism will moderate its profit orientation in the interest of the common good.

Countries like the PRC, Russia, Turkey and the Arab oligarchies engage in the suppression and even murder of dissidents at home and abroad, flouting international conventions when doing so. But that is a consequence, not a cause of the erosion of the liberal international order. The problem lies in that whatever the lip service paid to it, from a post-colonial perspective liberal internationalism was an elite concept with little trickle down practical effect. With global income inequalities increasing within and between States and the many flaws of the contemporary international trade regime exposed by the structural dislocations caused by Covid, the (neo-)Ricardian notions of comparative and competitive advantage have declined in popularity, replaced by more protectionist or self-sufficient economic doctrines.

Couple this with disenchantment with democracy as an equitable deliverer of social opportunity, justice and freedom in both advanced and newer democratic states, and what has emerged throughout the liberal democratic world is variants of national-populism that stress economic nationalism, ethnocentric homogeneity and traditional cultural values as the main organizing principles of society. The Trumpian slogan “America First” encapsulates the perspective well, but support for Brexit in the UK and the rising popularity of rightwing nationalist parties throughout Europe, some parts of Latin America and even Japan and South Korea indicates that all is not well in the liberal world (Australia and New Zealand remain as exceptions to the general rule).

That is where the redrawing comes in. Led by Russia and the PRC, an authoritarian coalition is slowly coalescing around the belief that the liberal international order is a post-colonial relic that was never intended to benefit the developing world but instead to lock in place an international institutional edifice that benefitted the former colonial/imperialist powers at the expense of the people that they directly subjugated up until 30-40 years ago. What the PRC and Russia propose is a redrawing of the framework in which international relations and foreign affairs is conducted, leading to one that is more bound by realist principles rooted in power and interest rather than hypocritically idealist notions about the perfectibility of humankind. It is the raw understanding of the anarchic nature of the international system that gives the alternative perspective credence in the eyes of the global South.

Phrased differently, there is truth to the claims that the liberal international order was a post-colonial invention that disproportionally benefitted Western powers. Because the PRC and USSR were major supporters of national liberation and revolutionary movements throughout the so-called “Third World” ranging from the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, Central and SE Asia to Central and South America, they have the anti-Western credentials to promote a plausible alternative cloaked not in the mantle of purported multilateral ideals but grounded in self-interested transactions mediated by power relationships. China’s Belt and Road initiative is one example in the economic sphere, and Russian military support for authoritarians in Syria, Iran, Cuba and Venezuela shows that even in times of change it remains steadfast in its pragmatic commitment to its international partners.

With this in mind I believe that 2022 will be a year where the transition from the liberal international order to something else will begin to pick up speed and as a result lead to various types of conflict between the old and new guards. What with hybrid or grey area conflict, disinformation campaigns, electoral meddling and cyberwarfare all now part of the psychological operations mix along with conventional air, land, sea and space-based kinetic military operations involving multi-domain command, control, communications, computing, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and robotics (C4ISR2) systems, the ways in which conflict can be engaged covertly or overtly have multiplied. That technological fact means that it is easier for international actors, or at least some of them, to act as disruptors of the global status quo by using conflict as a systemic re-alignment vehicle.

Absent a hegemonic power or Leviathan, a power vacuum has opened in which the world is open to the machinations of (dare I say it?) “charismatic men of destiny.” Putin, Xi Jingpin and other authoritarians see themselves as such men. Conflict will be the tool with which they attempt to impose their will on international society.

For them, the time is now. With the US divided, weakened and isolated after the Trump presidency and unable to recover quickly because of Covid, supply chain blockages, partisan gridlock and military exhaustion, with Europe also rendered by unprecedented divisions and most of the rest of the world adopting“wait and see” or hedging strategies, the strategic moment is opportune for Russia, China and lesser authoritarian powers to make decisive moves to alter the international status quo and present the liberal democratic world with a fait accompli that is more amenable to their geopolitical interests.

If what I propose is correct, the emerging world system dominated by authoritarian States led by the PRC and Russia will be less regulated (in the sense that power politics will replace norms, rules and laws as the basic framework governing inter-state relations), more fragmented (in that the thrust of foreign policies will be come more bilateral or unilateral rather than multilateral in nature), more coercive and dissuasive in its diplomatic exchanges and increasingly driven by basic calculations about power asymmetries (think “might makes right” and “possession is two thirds of the law”). International organisations and multilateral institutions will continue to exist as covers for State collusion on specific issues or as lip service purveyors of diplomatic platitudes, but in practice will be increasingly neutralised as deliberative, arbitrating-mediating and/or conflict-resolution bodies. Even if not a full descent into international anarchy, there will be a return to a Hobbesian state of nature.

2022 could well be the year that this begins to happen.

Update: For an audio short take on what 20022 may bring, please feel free to listen to the first episode of season three of “A View from Afar,” a podcast that offers a South Pacific perspective on geopolitical and strategic affairs co-hosted by Selwyn Manning and me.