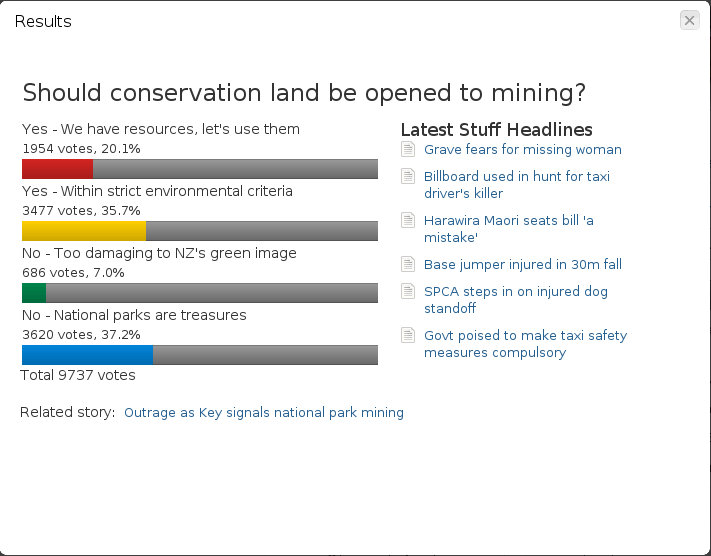

There’s been much analysis, wisdom, whimsy, and snark about Gerry Brownlee’s plans to mine the conservation estate. But rather than talk about it, I’m going to repair to a rather dubious poll from stuff.co.nz:

Two things are interesting about this poll. First, for an internet poll, the options are uncharacteristically nuanced. This leads to the second interesting thing: these results are deeply incoherent.

I’m going to work from two assumptions (both of which are pretty arguable). First, I’m going to go out on a limb and assume that stuff.co.nz poll respondents are pretty similar to NZ Herald poll respondents and the commenters on “Your Views” and Stuff’s equivalent — putting it very charitably, let’s just suppose that they’re somewhat further economically to the right, less environmentally conscious and with stronger authoritarian tendencies than Gerry Brownlee. Second, I’m going to assume that a poll like this should break roughly along partisan lines, since it’s a government policy opposed by the opposition, part of an overall strategy to mimic Australia, a complex topic of national significance with which people generally have little first-hand experience (the sort of thing they tend to entrust to their representatives), and the poll answers are heavily propagandised using the government and opposition’s own sorts of terms.

The poll result is incoherent because it doesn’t break along (rightward-slanted) partisan lines, although it initially looks like it does. A total of about 56% of respondents approve of mining in principle, and this is roughly what I would expect given this framing, the current government position on the topic, and the demographic characteristics of this type of poll. It’s what the government is banking on in terms of support with this policy: if it drops much lower, they’ll probably back down. But where it gets incoherent is in the other two options. The third option (“too damaging to NZ’s green image”) is about what the Green party is polling, and the fourth (“National Parks are treasures”) is about what the Labour party wishes it was polling. That’s bass-ackwards, because the third option is the Labour party’s actual position on many environmental matters (even Carol Beaumont’s passionately-titled post falls back on NZ Inc. reasoning), while the fourth position is the Green party’s actual deeply-held position of principle. A second source of incoherence is the political framing of the second (most popular) question. By definition, if conservation land is mined it’s not being conserved any more.

Both Labour and the Greens have huge opportunities here, but they need to position themselves to properly take advantage of them. Labour, for its part, needs to tone back the NZ Inc. reasoning which plays into all the assumptions of the second question: that it is a simple trade-off of one type of economic value against another type and come out looking good on the margin. This is classic trickle-up politics, rationale which appeals to the brain instead of the gut. The people who are picking options one and two probably think they’re doing so on solid rational bases: more money, more efficient use of resources, etc. — but the real reasons are probably more to do with ideology (mastery of the environment) and nationalism (catching up with Australia). Labour’s best move here is to appeal to peoples’ identity: New Zealanders think of themselves as people who live in a wild and pristine country, and they like having that country to go and ramble about in (even if they hardly ever do it). The Greens could also adopt such a position, abandoning the wonkery for things which matter to people. Russel Norman tried with his speech in reply yesterday, but I swear, whoever wrote it needs the ‘G’, ‘D’ and ‘P’ keys removed from their keyboard. He needs to take a few hints from the team who got an organic farmer elected to the Senate in Montana on an environmentalist platform by telling him to stop talking about environmentalism and start talking about how much he loved the land. The Greens also need to rethink their deeply confused firearm policy, but that’s a minor thing. In a country with such a strong constituency of outdoorsfolk and wilderness sportspeople it’s an absolute travesty that the MP who represents the hunting lobby is the urbane Peter Dunne, and the only party who genuinely values wild places is represented by earnest city-dwelling vegetarians.

But Labour and the Greens can’t divide this constituency between them; they need to make this appeal positive-sum, and steal back some of those who voted option two. The way to do this is to attack the implicit logic of option two, the idea that you can mine something and still be conserving it, and to remove the idea that this sort of thing is for a government to decide, that it’s somehow too complex or technical for ordinary people to understand. This shouldn’t be hard to do — it’s a plain old political education campaign. But it requires framing and a narrative whereby reasonable people can really only bring themselves to choose the wilderness; causing them to lose faith in the assurances of the government’s “strict environmental criteria”. The narrative needs to be about who we are in New Zealand, and it needs to be one which appeals to socially-conservative rural and suburban folk who would never think of voting for earnest city-dwelling vegetarians even though they share many of the same bedrock values. It needs to be like the lyric in the title: we are burning our furniture, and that’s not what civilised people do. New Zealand is not a nation of environmental degenerates, except when insufferable environmentalist smugness forces them to choose degeneracy as the less-bad identity position.

This is an issue on which the left can win, because it’s already a pretty marginal issue for the government. It cuts against a long-standing bipartisan reverence for National Parks, and it cuts against New Zealand identity as New Zealanders see it. Even on what should be a pretty reactionary online poll, the government only wins by 6%. Turn one in six of those people around and the issue gets put on ice for good.

L

I expect many people will reserve judgement until the actual sites are known. Cutting and pasting pictures of the likes of Mt Cook by the anti-mining lobby will soon wear thin, especially if a proposed site is in some scrubby gorse filled valley somewhere.

The battles will be won and lost entirely based on where the sites are going to be, not where the Greens pretend they are going to be.

And I agree with you about Norman’s incoherent speech. I’m still trying to work out if he really wants kids swimming in rivers instead of swimming pools, or whether this was just a runaway analogy.

My concern with the opposition to the mining is that the left is too fractionated. and not just the political parties but the activist left too. The gnats have a good strategy of ‘overwhelming’- so many issues to fight – which is the most important and they are also using the ‘assumptive close’ – I’ll assume you agree, and therefore do what I want, unless you explicitly disagree.

I think we need some big name NZers to stand up and say NO. A campaign around people that people know and all of the opposition must join forces (similar to the anti-tour movement) – that is maori, hunters, trampers, nature lovers, conservationists, – anyone and everyone.

The proponents of this must be made to feel very uncomfortable, personally. This is winnable and i know many people who will be down in front of the bulldozers if necessary.

The emotional connection we feel to this land must be pushed. Yes the facts and figures showing the idiocy of mining can be used but i tend to agree that people make decisions emotionally then justify them intellectually.

Pat, arguing the merits is a fallback position. A stronger strategy is to have voters reject the proposition outright on grounds of principle. Once you get into a discussion of the merits, it becomes a question of “how much” rather than “whether”.

I think some of the sentiments behind Norman’s speech were fantastic, both in terms of a strong symbolic appeal and in terms of actual policy. However he took it too far on both axes — opening himself up to being ridiculed as a primitivist, and bludgeoning the audience so mercilessly as to turn all but the converted away. This is the chief problem faced by the Greens: their inability to connect with peope who don’t already think like them. And someone needs to tell them: pick a better term than “GDP” to make your point on. It has no emotive resonance; that’s why people use it to make discussions of the economy clinical and mathematical, and to remove the personal aspects from the discussion — aspects which might cause people who are currently being screwed by the economy to reflect on that dissonance.

Marty,

Yes, there’s a strong “he iwi tahi tatou” argument to be made here, with white NZ being able to reference and appeal to the “rootedness” felt and expressed by tangata whenua without doing so in patronising or colonising ways. Mallard’s “I’m indigenous — I was born in Wainuiomata” has the right sort of sentiment, but was intended as a “one nation” dog-whistle and a justification for opposing tino rangatiratanga rather than an encouragement of everyone’s right to their land and identity.

L

The thing is Lew, as pakeha, you and I don’t have a right to the land – or at least, not just based on who we are. We have a right to it based on the Treaty, and our observation of the Treaty.

For a pakeha to express a rootedness that is equivalent, even if not identical to, the rootedness of an indigenous person is to create a false equivalency which undermines the unique nature of an indigenous person’s connection to the land, even if that claim isn’t used to directly oppose indigenous goals or claims.

Hugh, I can’t tell if this is what you genuinely believe or if you’re caricaturing my previously-stated views. I’ll assume the former.

I don’t suggest equivalence — not separate but equal as much as separate and different but meaningful nevertheless. I don’t think this necessarily undermines an indigenous claim, and indeed I think that such a sense of “rootedness” becoming politically institutionalised without being part of a “one nation” dog-whistle could be very beneficial for our national identity.

L

Lew, my views are generally that rootedness, particularly in the service of national identity, is a pretty bad thing. However, generally bringing up my views apropos of nothing is considered bad blogging etiquette, in my experience anyway.

However, if we make the assumption that rootedness -is- a good thing, I find it hard to square the idea that we can have two separate concepts of rootedness exercising equal political weight, but resting on very different foundations of historical tradition – different in the ‘one is shallow, one is not’ sense.

And from the perspective of this issue, is it really such a bad thing to accept my proposition? Saying ‘we shouldn’t mine here because it violates the sovereign rights of the indigenous people’ is, in my opinion, a stronger claim than ‘we shouldn’t mine here because of the natural splendor of the location’.

In other countries where mining is underway or under consideration and there is a strong indigenous presence still on the land the lead against the mining is from the indigenous communities. Here the land has been appropriated into “national parks” and other collective devices and the defenders against mining are not just or not even the indigenous people.

Whilst I quite like the angle from hugh that “we shouldn’t mine here because it violates the sovereign rights of the indigenous people’ i think we have to get the sovereign rights of the indigenous people sorted first – before that line would be successful.

Hugh, I certainly don’t accept the idea that nationalism and rootedness as a matter of national identity is an necessarily bad thing. But I think that’s a different discussion.

It would indeed be hard to square that circle. But that’s not what I’m suggesting — again, you use the word ‘equal’. What I’m saying is that, even if PÄkehÄ are not as rooted (this is a very unfortunate term, sorry) as MÄori, their rootedness, such as it is, still matters and should be acknowledged. Throughout my lengthy diatribes on the h debate I made this argument: that Laws and his lot have a valid claim, it’s just that they want their valid claim to extinguish a more-valid claim held by the local iwi. This position (that they had a valid claim) was acknowledged by the NZGB, the Whanganui MÄori and the crown, resulting in a resolution in which everyone claimed victory. In this case what I’m suggesting is that the two claims work toward the same goal, inasmuch as they share a common goal. Which I reckon they do — or they would, if the issue were appropriately framed.

In that sense, my appeal is not to “natural splendour” so much as the sovereign rights of New Zealanders as a group encompassing varied, overlapping claims to sovereignty (many of which have yet to be properly teased out).

L

Yes, well, that’s why I didn’t bring up whether rootedness is good, because it would be a derail. I can accept the proposition for the sake of the argument.

Firstly, I use the term ‘sovereign’ advisedly (although perhaps a bit loosely) to differentiate between the claims of the indigenous people and the settlers. The settlers’ claim is valid in the sense that it doesn’t need to be extinguished or ignored of right, but then again, the emotions of a tourist from Europe or Japan seeing the landscape for the first time are also valid; what they’re not is sovereign, as in they are born only out of a personal affection, not any part of the person’s culture. The only difference between the tourist and the pakeha is that the pakeha’s feelings towards the landscape are likely to be felt for a longer duration – a difference that might feel profound to the individual but which pales in comparison to that felt by the maori.

In essence we have two types of affection – tourists of various durations, and those whose home is truly here. Now you’re right, the feelings of the tourists aren’t invalid, but I’d say they’re basically irrelevant, and any dialogue needs to be very, very careful not to create false equivalence.

I think the minimum standard for not creating this false equivalence is to never mention the emotional ties of pakeha without also acknowledging the emotional ties of maori, and in doing so acknowledge that the ties of maori are stronger. This doesn’t invalidate the views of pakeha, it simply ensures they are always considered in the correct context.

Lew – applying the “False Mean” cartoon to the mining issue, you seem to firmly believe this is a kittens-in-the-blender issue. And therefore any mining in any National Parks is still putting some kittens in the blender. In most cases, I expect the vast majority of Kiwis would agree with that view.

But it will be hard to argue that a lower value, low significance piece of conservation land somewhere meets the kittens test. Many people would see it more like putting anchovies in the blender.

Hugh, I completely agree with your last paragraph, and I think I may have misunderstood your position on these sorts of matters in the past.

Pat, the thing about Schedule 4 is that none of it is “a lower value, low significance piece of conservation land”. If they want to mine other land, then that’s potentially a different matter. It may be as some have speculated that schedule 4 is a red herring, a strong opening bid from which National will be prepared to back down.

But again, that’s a debate on the merits, not one on principle.

L